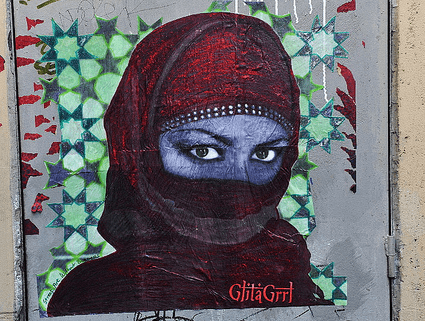

Lena Mohamed looks at the June 2014 judgment in the ECtHR over the French ban on face veils, arguing that the interpolation of an ill-defined right to ‘live together’, and the loss of the right of individuals’ to live and express their religion, highlights a culturally and politically loaded interpretation of the law and the failure of the Convention to protect minority citizens. It is of concern that similar sentiments are being expressed across Europe.

Background to the legislation

The Act of Parliament prohibiting individuals from concealing their faces in public was enacted by the French Senate in September 2010 following a virulent anti-Muslim campaign by the government, initiated by the then President, Nicholas Sarkozy, in his controversial 2009 speech.

In the wake of the 2008 global economic crash and the general decline in the President’s popularity, the need for a scapegoat and a distraction became manifest, and in a trend seen across Europe, Muslim communities were targeted.

In his speech, Sarkozy stated: “We cannot accept to have in our country women who are prisoners behind netting, cut off from all social life, deprived of identity. That is not the idea that the French republic has of women’s dignity. The burqa is not a sign of religion, it is a sign of subservience. It will not be welcome on the territory of the French republic.”

This rhetoric set out the parameters of the debate that would ensue. The burqa, a veil worn by some Muslim women that covers the face with a mesh across the eyes, was framed within the convergent ideologies of feminism, secularism, and nationalism.

The actual legislation did not make reference to religious clothing, and instead simply prohibited all facial coverings in public. However, the debate within both the media and the political arena revolved around the burqa and niqab. Therefore, while the act was framed in a way so as not to outwardly appear to discriminate against a minority group, in the minds of politicians and the general public that certainly appeared to be the intent. When the immigration minister referred to the burqa as a ‘walking coffin’ and the Prime Minister claimed the image of it painted a ‘dark and sectarian image’ it was clear that the primary target of the legislation was indeed the veil.

Despite concerns raised by the French Council of State that the legislation could conflict with international human rights law, the Act was passed by a vote of 246 to 1, with 100 abstentions, on a wave of popular public support with surveys recording an approval rating of eighty-two percent.

Background to the case

In reaction to the passing of this law, a young French woman brought a claim against the State for breach of her human rights. She wore the burqa (full body covering with full face veil and mesh covering the eyes) and niqab (full face veil with an opening for the eyes) as an expression of and in accordance with her faith.

As it was her choice to wear these items of clothing, she objected to the infringement by the state on several of her rights under the European Convention on Human Rights (“the Convention”) as enacted under French law. Her legal team argued that her Article 3 (prohibition of torture or inhuman or degrading treatment), Article 8 (right to respect for private and family life), Article 9 (freedom of thought, conscience and religion), Article 10 (freedom of expression), Article 11 (freedom assembly and association), and Article 14 (prohibition of discrimination) rights were either actually being infringed and/or potentially stood to be violated by this law.

The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg was required to consider whether these rights had in fact been infringed, and if so, whether the detriments the plaintiff faced outweighed the detriment to the ‘public good’.

On 1 July 2014, in a majority judgment, the Grand Chamber rejected her application, finding that the French government had not breached the Convention in enacting this legislation. The Grand Chamber is the ECHR’s highest forum and consists of 17 judges. Two judges partially dissented from the majority opinion concluding that the applicant’s Article 8 and 9 rights had indeed been violated.

Articles under the European Convention on Human Rights

The Convention Articles discussed at length in the judgment are outlined below.

Article 3: Prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment

The applicant complained that the law would leave her open to criminal sanction if she refused to abide by its oppressive restrictions, thus imposing a degrading experience on her.

This was not accepted by the court to be a strong enough argument of ill-treatment on her part, and thus it was determined that Article 3 had not been breached.

However, the decision highlights the way in which Western cultural norms and practices are being imposed on all members of society with little regard for the minority experience. This is despite the Convention’s commitment on paper to protect individuals’ rights to their particular practices even when it goes against the grain of majority opinion.

In a multicultural and multi-religious society such as France it is inevitable that standards of modesty will differ from person to person. If one is driven by a particular moral code in determining how to present oneself to the wider world, then it is a violation by the State when that choice is removed. It results in a degrading experience for the victim because he/she is not at liberty to live by that moral code.

Article 8: Right to respect for private and family life

This relates to the Article 3 reasoning, where the applicant argued that the personal choices made related to her personality, and thus fell within the definition of ‘private life’. Additionally, this qualified right allows for personal autonomy and the right not to be interfered with physically or psychologically. The way in which one dresses is a deeply personal issue and is a statement of identity just as much as the person who wears, for example, dark sunglasses and/or tattoos. However, the applicant’s act of self-expression has the added feature of faith, another marker of identity.

Forcible removal of the burqa or niqab would violate this and potentially cause the same kind of deep psychological distress caused by the ban on headscarves in French schools. IHRC’s report on the impact of the headscarf ban in French schools highlights the trauma experienced by young girls forced to remove a symbol of their faith as well as abandoning their conception of modesty and decorum. A similar experience could be expected in this case too.

Article 9: Freedom of thought, conscience and religion

The qualified right to freedom of religion includes the right to manifest one’s religion in public through practice and observance. The applicant’s right to wear the niqab or burqa falls squarely within this right.

The judgment

The Court, while dismissing Articles 3, 10 and 11, agreed that Articles 8 and 9 were engaged by imposing limitations or interferences in the life of the applicant. As these rights are qualified and not absolute, such interferences can be justified by the State if it can show a ‘legitimate aim’ and one that can be seen as necessary in a democratic society.

The French government argued that the legislation banning face coverings in public spaces pursued two legitimate aims: that of public safety, and ‘respect for the minimum set of values of an open and democratic society.’

Public safety

In its submissions as well as in the debates prior to the passing of the law, the government played heavily on the supposed threat the niqab and burqa posed to public safety. It identified the need to prevent danger to persons and property and to combat identity fraud, all of which are risks when an individual’s face is concealed.

However, IHRC would contend that a blanket ban on face coverings is not a legitimate aim in the preservation of public safety and security. The applicant herself raised no objections to the possibility of showing her face in instances where threats to property or persons became apparent. If such exceptions could be made, then the infringement of the rights of this minority of women could be avoided.

Respect for the minimum set of values in an open and democratic society

The government’s argument was based on a report produced by a French parliamentary commission in 2010 which, at its crux, contended that the concealment of the face is problematic because ‘it is quite simply incompatible with the fundamental requirements of ‘living together’ in French society.’

The idea of ‘living together’ is not a right that is protected within the Convention. It is a vague concept that alludes to the desire to establish social cohesion. However with the implementation of this law it became clear that social cohesion is something that the State wishes to impose on its citizens, rather than encourage.

The discourse around ‘living together’ implies two important themes within contemporary Western culture. The first is that all citizens are required to participate fully in society, and the second that one must interact with all fellow citizens.

There is no basis whatsoever to such assertions by the government. It is apparent that, in reaction to the burqa and niqab, the media and policy-makers have fabricated a particular aspect of Western culture where the primary mode of communication is via eye contact and facial expressions. When women wearing these items of clothing do not engage in this so-called essential element of social life in France, they are deemed to be jeopardising the concept of ‘living together’. As the dissenting judges pointed out, ‘people can socialise without necessarily looking into each other’s eyes’.

It is clear that the French government has interpreted the concept of an ‘open society’ as one in which all members of society have unfettered access to each other. However, the right to respect for private life would undoubtedly include the right not to communicate with others in public spaces, and not to participate in social activities if one desires as much. The emphasis on enforced participation suggests a rather ominous lurch towards an authoritarian state that is concerned with controlling the actions of its subjects.

It also flies in the face of the concept of a ‘democratic society’, which by its definition must be inclusive of divergent opinions and practices, as well as ensure the ability of minorities to express these without fear of oppression or demonisation. IHRC disagrees with the ECHR judgment: in our view the French government has clearly violated the rights of Muslim women who wish to veil their faces as a manifestation of their religion, a right protected under the Convention.

The judgment in context

These two key arguments, in IHRC’s estimation, fall short of the requirements necessary to demonstrate the legitimate aims of a law that violates the rights and liberties of Muslim women who choose to wear the niqab and burqa. The rights of the individual to practise their religion and express their identity are protected within the Convention. A breach of these rights can only be justified if the rights of the wider public are jeopardised by their exercise. The risk to public safety could be overcome with simple, incident-specific measures. In addition, the concept of ‘living together’ and social cohesion is an arbitrary one that, even if suitably defined, cannot logically be threatened by the approximately 1900 women in France who choose to veil their faces.

IHRC would therefore assert that the legislation is not about preserving the public good, but rather has the very specific aim of forced integration and the demonisation and elimination of communities that resist attempts to coercively shape their identities.

France, and Europe as a whole, have historically had a relationship with Islam that framed Muslims as ‘the Other.’ This was true of both Muslims in the ‘Orient’ and those in European lands. This rhetoric is still present today, and demonstrates the fear and loathing for Muslims at the heart of the white supremacist Western nation state.

This law is particularly illustrative of this point, perpetuating the myth that white men – the legislators and media pundits (still by and large men) – must have access to the bodies of brown women to enforce the hierarchy of his racial and sexual dominance. By forcing a woman to unveil herself, despite attestations that she wants to remain covered, he is living out his neo-Orientalist fantasy as well as fulfilling the goal of forced assimilation. Forced assimilation ensures that Muslims are not able to practise their faith in the open and are therefore not a visible threat to the European way of life.

This is not a one-off policy either. It is part of an attempt to systematically marginalise minority Muslim communities. This briefing has already drawn attention to the headscarf ban in schools in France. Since the French precedent, the banning of the burqa is a policy objective that has gained traction in other countries across Europe. In the United Kingdom for example, there was a recent private members’ bill that attempted to introduce into law a similarly-worded piece of legislation to that of the French version. Similarly, the recent media storm over the issue of halal meat is indicative of the kind of hysterical Islamophobia that is sweeping Europe at an exponential rate. This particular matter relates to animal slaughter and food consumption, the ethics of which have been supported by much academic research. It is also a matter that is ostensibly one for Muslim communities and animal rights activists to negotiate, yet has been hijacked by the mainstream media and those in positions of power.

These developments highlight the use of the rights agenda to further marginalise Muslims in Europe. Just as animal rights discourse was adopted in the halal meat debate (despite little to no engagement in the issue of animal welfare in mainstream slaughterhouse practices), women’s rights were adopted in the ‘burqa ban’ debate in France. In Western conceptions of women of the ‘Orient’, they are either exoticised or they are oppressed. The burqa is an image the West has used to support the latter. IHRC fully acknowledges that some women are put in positions where they are forced to wear the burqa or the niqab and unequivocally denounces this practice. However, this is by no means the dominant experience of most niqab or burqa-wearing women, with many demanding an end to discriminatory rhetoric that calls for them to be ‘saved’ by the State. (An example is Nicholas Sarkozy’s 2009 description of the burqa as an item of clothing that ” imprisoned [women] behind a mesh, cut off from society, deprived of all identity. That is not the French republic’s idea of women’s dignity.”)

Additionally, politicians have attempted to reconstruct Islam as lived and believed by Muslims, claiming that those who wear veils covering their faces were ‘hijacking Islam’ (Francois Fillon, French Prime Minister) and that the ‘full-face veil was not required by the Koran but corresponds to a minority custom from the Arabian peninsula’ (Belgian government intervention). By defining Islam themselves and denying this right to those who practise the faith, politicians create a situation in which Muslims are excluded from Islam as experienced within the State.

The arrogance of this attitude of the State can be seen in the way the French government was surprised to hear the applicant’s argument that she wore the burqa and niqab of her own volition and found it to be an empowering garment that allowed her to resist attempts by the media and society at large to ‘possess’ her body.

In addition to this perceived audacious expression of religiosity (something to be resisted at all costs within the French secular consciousness), the visibility of the burqa and niqab also contributes to accusations in the West that Muslim communities are becoming more radicalised. In fact, the dissenting judges acknowledged that this legislation targeting the Muslim face veil demonstrates not a commitment to ‘living together’, but rather shows a prejudice for the ‘philosophy that is presumed to be linked to it [the veil].’ That the increased visibility of ‘Muslim-ness’ in public spaces is perceived as a threat goes some way to understanding the Western attitude to ‘the Other’. It also demonstrates a profound lack of understanding of the impact of the State’s policies on its civilian population. Labelling Muslims as ‘radical’ simply because of the clothes they wear is short-sighted and damaging and misses the point that aggressive European neo-colonial foreign policy in Muslim lands is predominantly to blame for most anti-Western sentiment espoused amongst young Muslims. It also misrepresents the threat of ‘Islamic terrorism’ as the major problem facing Europe today, when official statistics show the rise of far right terrorism to be the continent’s greatest threat.

This constant harassment of Muslims by the media and policymakers in Europe is demonstrative of the attempt to forcibly assimilate them into Western society. It does not allow for religious or cultural diversity as such projects threaten a way of life that seeks to maintain white liberals in positions of authority at the exclusion of everyone else.

Failure to assimilate comes at great cost. Such Muslims are ‘encouraged’ to ‘disappear’ from public life. For example, approximately seventy percent of the prison population in France is Muslim, despite only accounting for ten percent of the entire population. In the UK, the Muslim prison population has doubled in the last decade. If the state cannot find legal means to incarcerate Muslims in their home country, it is increasingly looking to extradite or deport them, as the UK has done with Babar Ahmad and Talha Ahsan. The implication is that if one refuses to conform to the normative ideals of the western State, then one will be locked up or forcibly removed. Such policies deny the legitimacy of diversity, as enshrined in the concept of democracy and in the Convention itself.

The legislation used to extradite Ahmad and Ahsan is just one in a series introduced since 2000 as part of the so-called ‘war on terror.’ With the criminalisation of, among other things, what Muslims read, watch and think, the legislation forces them to adhere to the desired political narratives constructed by the government. It allows the State to define what constitutes a ‘good Muslim’ (one who conforms) and what constitutes a ‘bad Muslim’ (one who asserts his or her political and religious agency). This again is part of the systematic de-legitimisation in the West of alternative views and ideas, and impacts directly on minorities.

The attempt to forcibly assimilate Muslims creates a scenario whereby Muslims are positioned in opposition to white populations in the West who enjoy the rights protected by the Convention. The operative principle appears to be that Muslims are backward and must forcibly be changed or failing that, removed from the community. This attitude is reflected in the judgment of the Court, where the moral and ethical dimension of a Muslim woman’s existence is seen as subordinate to the desire to protect western liberal ideals.

The debate around the veil has thus been positioned in France within the context of nationalism and the State’s belief in liberté, egalité and fraternité. It is clear that in France’s construction of its own identity, it has excluded the Muslim minority in a history that goes back to its colonial era, where mainly Algerian, Moroccan, and Tunisian subjects, although French, did not have the same rights as their white French counterparts. As a result, it is not possible for Muslims to be included in its constitutional motto, and it is therefore not possible for them to be afforded the same rights under it. The Court’s decision to uphold the ban is therefore in keeping with this particular historical narrative.

It is clear that the decision of the Court fits neatly within a European nationalist narrative that has at its core the exclusion of minorities from society. The interpolation of an ill-defined right to ‘live together’, and the loss of the right of individuals’ to live and express their religion, highlights a culturally and politically loaded interpretation of the law and the failure of the Convention to protect minority citizens. It is of concern that similar sentiments are being expressed across Europe. As the Court has now established a precedent, the door is open for other states to enact similarly oppressive measures.