“When we found ourselves at last taken away, death was more preferable than life; and a plan was concerted amongst us, that we might burn and blow up the ship, and to perish all together in the flames . . . It was the women and boys which were to burn the ship, with the approbation and groans of the rest; though that was prevented, the discovery was likewise a cruel bloody scene.“

Ottobah Cugoano describing the attempted revolt organized on the ship that took him from the Gold Coast to Grenada

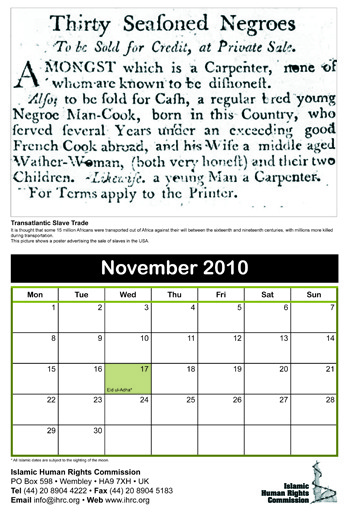

As one of the most sustained and brutally efficient systems of bondage which the modern world has seen, the transatlantic slave trade is unparalleled in severity. Over the course of more than three and a half centuries, over twelve million men, women and children were transported- under duress- to the Americas as a source of free and forced labour.

The legacy lingers

The direct impact of the African slavery can be felt today as the trade was lucrative and successful in generating immense wealth for America and Europe’s business interests. Many argue that this flourishing of intense and free labour laid the foundations for modern capitalism as forced human toil paid dividends for American and European beneficiaries. As always, a flipside exists and so whilst slavery accelerated the industrialisation of northwest Europe, North and South America- the impact on Africa proved infinitely devastating. With the loss of a great portion of Africa’s young and able-bodied population, the country’s economic, educational and political systems fast degenerated. During this vulnerable time, the weakening of Africa’s social institutions made easier colonial domination and resource-exploitation; realities which defined nineteenth century Africa.

The echoes of over 300 years of transatlantic slavery remain today in many more subtle ways also, not least through the millions of men and women of African descent who now reside all over North and South America. There also remain countless descendents of African slaves who still bear the European surnames of their ancestors’ slave masters.

This essay will explore the historical context of transatlantic African slavery as well as an analysis of the motives for its establishment and factors which lead to slavery’s official abolition in the United States in 1865 CE.

In the beginning: Motives

In the age of expanding empires, the middle of the fifteenth century saw Portuguese trade ships sailing down the West African cost looking for maritime discoveries and hoping for advances in ship building. Since North Africans held a tight monopoly when it came to trading exotic spices and sub-Saharan gold, these Portuguese ships found themselves sailing westwards. These voyages proved fruitful as those on board acquired the necessary expertise in ship building to pass onto fellow European travellers- who then created vessels much more efficient in navigating the Atlantic.

As access to African mainland had become easier, one important resource which the European empires in the ‘New World’ lacked in their own countries was a strong work force. Back in their own countries, workers were thought of as unreliable, often ‘not built’ for intense outdoor physical labour and prone to many of the tropical diseases which were brought over from Africa. An irresistible solution to this problem came as the Portuguese focused their attentions on Africans and soon enough, African workers were added to the slave ships together with all other commodities being transported. The Portuguese thought of Africans as ‘excellent workers’ due to their familiarity with agriculture and experience in keeping cattle. The new workforce also were used to the tropical climate and resistant to the many diseases which Europeans were thought too weak for. As such, workers were also rumoured to be ideal for working ‘very hard’ on plantations and mines as this was thought of as the ideal work for the Africans.

The early years: chosen destinations and through the phases

For the first hundred years of the three hundred year trade, ships took only small numbers of captives to transport to Europe. Eventually, at the turn of the fifteenth century these numbers began to add up until over 10 percent of Portugal’s largest city Lisbon was made up of Africans. Lisbon was not the only intended destination however, and Portuguese ships took African slaves to offshore islands such as Madeira, São Tomé and Cape Verde. Here, sugar plantations were established and this early labour of the slaves was an eerie foreshadowing of what would become much larger-scale enterprise in plantation slavery in the Americas. As the ‘success’ of this forced labour was becoming known, European ships varied the places, fields and plantations where they would take the Africans and soon enough, you found slaves across North Africa, Persia, India, the Indian Ocean islands, the Middle East and in Europe as far as Russia.

Portuguese trade ships were closely followed by English and Dutch traders who too, wanted to monopolise on this source of free and lucrative African labour. With growing competition between the European empires, Portuguese ships soon found themselves preyed upon by English and Dutch vessels. Despite intense in-fighting, all European interests were unified in the common cause of pillaging and raiding the African mainland as soon as their ships docked.

From 1492 onwards, human slave trafficking had become the norm on trade ships and Africans became an essential part of ‘goods’ which took up the expeditions into the soon-to-be American Spanish colonies. This continued unabated until the beginning of the sixteenth century when slaves were bought specifically to grow sugar and mine gold on the then-named ‘Hispaniola’. In a feat of harsh irony, Africans were forced to do jobs like drain the shallow lakes of the Mexican plateau and to perform tasks which would help their slave masters advance the genocide of the indigenous Native American population. Little did they know at the time, but the work they carried out in subjugation made it easier to subjugate another people in the future.

With the trade in full force, the middle of the seventeenth century saw a more intense phase of activity: the creation of grand-scale sugar plantations and the introduction of new crops such as indigo, rice, tobacco, coffee, cocoa and cotton. As ambitions for slave-activity grew, so did the numbers of displaced Africans. In fact, between 1650 and 1807 over seven million slaves had been displaced in order to meet the burgeoning demand for labour. The beneficiaries of all this new-found labour was not just limited to ship traders and land owners, but the trade invited a mix of opportunists and entrepreneurs who seized the chance of making an easy profit. The inevitable knock-on effect of this was that larger parts of Africa were being targeted for sourcing more human labour, so by now large parts of West and Central Africa had fallen into the so-called ‘slavers orbit’.

The final period of the slave trade was instigated by the ban on ‘importing’ slaves by Britain and the United States- this ban began in 1807 and lasted until 1860. Though many are the first to cite Britain as the first to attempt to abolish slavery, it is often overlooked that Britain was also the worst perpetrators of slavery in this period. During the eighteenth century when slavery was at its peak, Britain transported a staggering 2.5 million of the 6 million slaves displaced overall.

Countries like Brazil, Cuba and Puerto Rico now suddenly became the slave destination of choice since official legislation had abolished slavery in North America, British and French colonies in the Caribbean and independent countries like Spanish America. Contrary to what many had thought, this restriction did not slow down the number of slaves being forced out of Africa and many were secretly smuggled into the United States well after the 1840s. Those Africans who were found on now-illegal slave ships were also still not allowed to return to their countries, but rather forcibly resettled on several islands of the Caribbean and countries like Sierra Leone and Liberia.

Conditions on the ships

Long before the slaves reached the site of their plantations or even got to their slave owners, many died on the voyage there. The majority of the deaths on ships across the Atlantic happened within the first fortnight of setting sail. Deaths were caused by new diseases which were introduced to them aboard because of malnutrition and disease through forced marches and internments on slave camps. The estimated death rate for slaves was 13 percent aboard the ship, significantly lower than the mortality rate for fellow seamen and passengers on the very same voyages.

Trading for human life

When European and American slave traders could not afford to purchase men, women and children with money, they instead exchanged goods ‘on credit’ whilst they weren’t able to send cash. Slave traders would send a range of commodities to Africa in exchange for captives and these included cowry shells, strips of cloth, iron bars and copper bars as well as finished consumer goods such as textiles, alcohol and jewellery. Many of these items were considered to be ‘compensation’ the local communities who had lost people and in many parts of West Africa, alcohol was gratefully received. In smaller ports like the Upper Guinea Coast, merchants would often hold remaining relatives of slaves as ‘ransom’ if ship captains were not able to pay in case for their goods. These individuals effectively functioned as human pawns that were then offered as slaves if debts were not paid.

The triangular trade: Profit at every stage

The trading of goods, taking of slaves and exchanging of goods was a multi-tasked operation which reaped benefits for many parties at every stage. A term for the three-way ‘triangular trade’ was coined which described the various stages which merchants and slave-traders went through.

The first of the three stages involved merchants taking ready-manufactured goods from Europe to Africa to sell to local populations or- as discussed earlier- to use as ‘credit’ to buy slaves with. Part of the goods taken involved guns, though these were not widely popular as it was difficult to keep gun-powder dry in tropical climates. Once the guns had arrived to the coast of Africa however, they were used in civil unrest and to threaten communities into giving up more people to become slaves. Rarely did the merchants pay for slaves in cash; rather they exchanged these commodities for slaves.

Once the Europeans had given out their goods and collected back in slaves, the second part and middle part of the ‘triangular trade’ was the process of taking these slaves to the Americas. Whilst in the Americas, the slave ships would stock up on the produce from the slave-labour plantations- mainly consisting of cotton, sugar, tobacco, molasses and rum.

This middle passage lasted varying times, from one month to three months. Despite regulations restricting passenger numbers to 350, many boats carried upwards of 800 men, women and children. The majority of passengers were not allowed room to stand or be clothed, many were branded, stripped naked and were forced to lie down, invited occasionally to ‘dance on deck’ in order to keep their limbs straight. The Middle Passages took place during the summer months, so the spread of disease was exacerbated by intense heat.

Despite this, ten million people were able to survive the ‘middle passage’ and of these, 450,000 made it to North America’s shores. These slaves represent only 5 percent of the slaves which were displaced from Africa through slavery’s 350 year history. Though lesser known, Brazil and the Caribbean each received over nine times as many Africans as North America did.

Once the slaves had been ‘deposited’ to their destinations, the raw goods aboard the boats would form the third and final stage of the trade as slave owners returned to Europe with these raw goods. Whilst in Europe, the goods would be manufactured into finished products and the first stage of the triangular trade would be ready to begin again.

Many of the slaves from taken Africa were taken from Senegambia and the then-named Windward Coast. As time wore on, the 1650s saw the slave trade moving to west-central Africa to several distinct regions were identified and distinguished by the particular European countries who visited those specific slave ports, the people who were enslaved and also, the dominant figures in African societies who happily provided the slaves.

In total, there are records of over 30,000 voyages made between Africa and the Americas throughout the three centuries of the transatlantic slave trade. We rely on private records to provide detailed information on the real brutality of the slave trade, but statistics and numbers alone cannot possibly convey the injustices and brutalities faced by the enslaved populations.

Complicated endings, crippled futures

Article I, Section 9, Clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution (1787) stipulated that “The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person.”

Though the United States officially abolished its slave trade from Africa on January 1, 1808, an illegal slave trade remained active until 1860. American slave ships continued to ship Africans to South America where the slave trade was still legal in Cuba, Puerto Rico and Brazil. The trade of slavery was still so intact that during 1801 and 1867, a staggering 3.3 million Africans were transported to South America.

The end of the slave trade was a slow, splintered and often insincere process- however the impact the whole 350 year trade had on Africa remained stark. At every level of African society (from personal, to family to communal to economic) you can see the devastating effect of transatlantic slavery. Africa continues to reel today from the consequences of having millions of their able-bodied individuals seized and enslaved into foreign lands. To this day, wars, slave raids and civil unrest continue to haunt Africa’s reality. It is important for this reason to keep the bitter memory and horror of experience alive in our thoughts and conscience.

{jathumbnail off}