[15 December 2017] The line between Palestine and North London is not such a very long one. There is a moment early in the film, Those Glory Glory Days, when sports journalist Julie Welch stumbles upon her childhood idol, Danny Blanchflower, as she returns to White Hart Lane to report on a Spurs tie. Cue flashback to 1961 and the summer Spurs won the double.

Aged 12 when that film was screened on Channel 4, it can’t have been that long after (though as a teen it seemed forever) that I, too, bumped into a footballing legend, none other than Gary Lineker, in the grounds of said stadium.

Utterly charming, natural and beaming that radiant smile, he was speaking with fans and signing autographs. Me? Gripped in the all-encompassing passion of a die-hard fan, I blanked him because in those days Lineker was part of the dreaded Everton, whose contemporary successes Lineker had been crucial to, and was diametrically opposed to our own.

It makes no sense in retrospect (as indeed it didn’t to many Spurs fans around me) but it is an example of how the obsessive gaze of “tribe” or “nation” can seize hold. A series of irrational beliefs and emotions that will make us see right as wrong or wrong as right.

John Berger and Laura Mulvey have written extensively on how this affects women (something Welch had to battle in her desire to be a sports reporter). Edward Said is perhaps the most famous of those who describe this process vis a vis the “Oriental” other, but the list is long.

For a comprehensive overview of how those hierarchies are constituted, and organised by “race”, watch Ramon Grosfoguel.

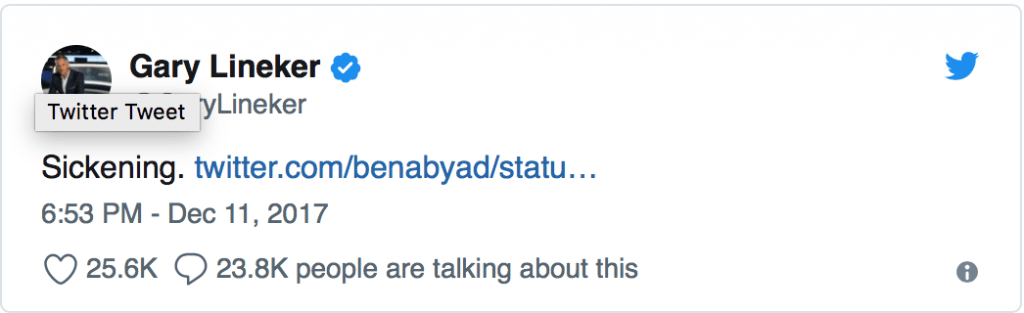

And that is the point at which Lineker has so spectacularly entered the story of Palestine this week, when he retweeted a BT’Selem video showing a Palestinian child being caged by Israeli soldiers. “Sickening”, he said.

Wrapped up in the to and fro of the fight that ensued in the Twittersphere between Lineker and the former Israeli army spokesperson Peter Lerner, and the glory attributed to Lineker’s interventions, the key question raised was lost. How was Lineker’s comment even contentious?

When it comes to the demonising gaze, Palestinians know better than most the devastating impact that can have. Variously otherised as Muslims, Arabs, terrorists, even the name Palestine has been made to symbolise violence and degeneration in the ways of colonisation, rewritten for a supposedly post-colonial era.

And no one in Palestine has suffered the impact of that gaze more than its children.

As many Palestinians and their allies noted, the image of 16-year-old Fawzi al-Jundeidi, blindfolded and frogmarched to detention, with at least 20 Israeli soldiers surrounding him, is nothing new.

It wasn’t new when the NGO Defense for Children, was set up 25 years ago to advocate for the tens, dozens and hundreds of Palestinian children detained by the Israeli army (often without charge often sexually and or physically abused). It wasn’t new when UNICEF reported on it.

It wasn’t new at the time of any of the intifadas or indeed at the time of the Nakba. This has been the modus operandi of this particular occupation and yet very few for the longest of times within Westernised narratives and settings were able to either see this – or felt safe enough to articulate it. Since 2000, there have been 10,000 children detained. The figure currently runs at 700 children detained per year.

Both the power of the gaze and the perilous position of those who wish to resist it, whether in spoken solidarity in European(ised) metropoles or by throwing a stone at an Israeli tank on the ground in the West Bank, have meant that Palestinians generally, Palestinian aspirations, and Palestinian children in particular have been effaced from all conceptions of the moral.

Last summer, the annual pro-Palestinian protest and rally in London was hit by a vicious campaign. When one of the speakers addressing the rally spoke of the sexual abuse of Palestinian children in Israeli prisons, I heard a roar of cheers from the unusually large and abusive counter-demonstration.

None of this was reported in any mainstream media.

Prior to the event the counter-campaign had sought, largely online but also through some specialist press, to claim that the protest would have “terrorist flags flying”. It was widely reported, though not confirmed, that the alleged Finsbury Mosque attacker, Darren Osborne,came to London, in his own words, to do something about the event.

Whether he was too late or simply couldn’t get through the police cordon we don’t know, but this is how the gaze works to directly and indirectly commit and perpetuate violence. If this is the violence levelled against solidarity movements in the UK, imagine what it is on the streets of Palestine?

Farah Nabulsi’s recently released short film, Today They Took My Son, shows with great force how this plays out for Palestine’s children. Children, who despite imprisonment, torture, maiming and many other types of abuse, continue to resist – with at best words and stones – one of the most powerful armies in the world.

Currently I am working on the University of Leeds led project on counter-narratives to Islamophobia. The biggest question facing the researchers from all the countries involved in this Europe-wide study is how exactly to break the hold of the Islamophobic view of the world that currently holds sway?

Solidarity is one, and Lineker has done that and stood by that and empowered that narrative. However, what is more important is giving the voice of the oppressed themselves the space it needs to be heard.

Whether you are highly paid football or TV personality, or an activist, your job is to withstand that demonising gaze however hard so that there can be a space for the narrative of justice for the Palestinians and all oppressed peoples.

Our acts are important, and our struggles won’t be easy, but be under no illusions: it is the children of Palestine that are the heroes and all the glory is theirs.

-Arzu Merali is a writer and researcher based in London, UK. She is one of the founders of the Islamic Human Rights Commission, and formerly editor of the web-journal Palestine Internationalist. Her latest book, co-authored with Saied R. Ameli is Environment of Hate: The New Normal for Muslims in the UK.