Les Levidow overviews the attempts to normalise and integrate IHRA, and offers some strategic observations.

Acknowledgements: This article extends the author’s talk at the IHRC conference, ‘Islamophobia and Silencing Criticism of Israel’, 15 December 2019. It was published in the January 2019 Newsletter of the British Committee for the Universities of Palestine (BRICUP).

[Published in the IHRC website, 2 February 2019, download the PDF here] With the increasing mobilisation of Far Right forces in recent years, antisemitic attacks have become a more serious threat. However, a high-profile campaign has disgracefully targeted an ‘antisemitism problem’ in the Labour Party and the wider Palestine solidarity movement. For nearly three years, the movement has been countering the false allegations.

Despite our great efforts, the intimidation campaign has remained pervasive and stable. How and why? It has systematically elided the categories of Jew and Zionist. Moreover a prevalent stereotype of the Jew-as-Zionist, consequently vulnerable to antisemitism, provides a shield and displacement for the state’s pro-Israel commitments. The institutional drivers and strategic implications are discussed in this article; see hyperlinks and References list for documentary sources.

‘Offence’ conflated with antisemitism

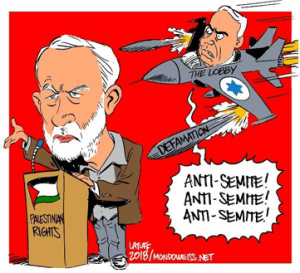

Since spring 2016 there has been a high-profile, escalating campaign of false allegations against pro-Palestine activists. A prime target has been the Labour Party, with allegations that its leadership had failed to address its alleged internal antisemitism problem. The Palestine solidarity movement has responded by distinguishing between real antisemitism, and false allegations which weaponise antisemitism to protect Israel, not Jews.

logo at www.freespeechonisrael.org.uk

In the intimidation campaign, a key weapon has been the so-called ‘IHRA definition’, misnomer for a long document. Although the short definition was approved by an IHRA meeting, its website subsequently posted a long guidance document that lacks endorsement by any international body. The long document has 11 examples, 7 referring to Israel, some conflating antisemitism with criticism of that state. In particular, it is supposedly antisemitic to describe the Israeli regime as ‘a racist endeavour’; consequently, the phrase ‘apartheid Israel’ becomes a taboo. On this basis, the guidance document has served to censor speech and deny venues for events, especially in universities during Israeli Apartheid Week. Efforts to counter the intimidation campaign have been informed by Jewish-led pro-Palestine groups, especially Free Speech on Israel and more recently Jewish Voice for Labour (see References).

Despite our protests, politicians have generally evaded any engagement with the dispute over what constitutes antisemitism. Instead they accept purely subjective criteria, namely: a remark is antisemitic if a Jewish person claims that it is. Often politicians conflate antisemitism with any comments ‘offensive to Jews’, often corresponding with Israel examples in the IHRA document.

To justify these subjective criteria, ‘the Macpherson principle’ has been cited by diverse politicians such as New Labour MPs and Caroline Lucas of the Green Party (despite its official support for the BDS campaign). Thus they distort Macpherson’s recommendation that any claim about a racist incident should be properly recorded and investigated – not that the claim should be automatically accepted. In this way, politicians conveniently avoid any responsibility for judgements about what is or is not antisemitic, as well as any responsibility for the IHRA guidance as a political weapon.

Since 2016 the intimidation campaign has united diverse political forces (the UK government, the entire mass media, most of the Parliamentary Labour Party, etc.) around a common motive to undermine the pro-Corbyn leadership of the Labour Party. By mid-2018 that leadership had replaced its anti-Corbyn General Secretary and consolidated its control over the Labour Party administration. Nevertheless it is still formally investigating pro-Palestine members for statements which ‘cause offence’ (often related to IHRA examples) and thus supposedly ‘bring the Party into disrepute’.

Israel lobby: hijack or partner?

How to explain such broad, enduring cross-institutional complicity with the intimidation campaign? Has the Israel lobby hijacked British institutions? Efforts to do so were well documented by the 2017 Al Jazeera exposé of Israeli funding for lobby groups within the Labour Party. As another example, the UK counter-extremism Prevent programme has actively stigmatised and suppressed criticism of Israel as ‘extremist’, thus appearing to serve that regime.

Rather than an Israeli hijack of UK institutions, however, the situation can be understood nearly the other way around, namely: the Israel lobby’s power has always depended on the agenda and power of the British state in the broad sense. In particular we have seen the following: government Ministries trying to prevent boycotts of Israel (or of complicit companies), political parties disciplining members on false grounds, university administrations trying to deter Palestine solidarity activities; and Local Authorities dismissing staff for anti-Israel statements made outside of a work context. These executive actions encourage more false ‘antisemitism’ allegations by pro-Israel groups, which thereby gain the deceptive appearance of great power.

This partnership between the Israel lobby and British institutions continues their long-time role in protecting the Zionist colonisation project since a century ago. Back in 1916 Jerusalem’s first British governor envisaged a future Jewish state as ‘a little loyal Jewish Ulster in a sea of potentially hostile Arabism’. Indeed, Western powers still depend on Israel for counter-insurgency against independent political forces in the region. This original driver in British imperial interests (and later neo-colonial strategies) continues today, more recently reinforced by the UK’s pervasive deference to US foreign policy.

As an extra driver, the European military-industrial-academic-security complex has been increasingly integrated with its Israeli counterpart. This freely uses Palestine as a convenient laboratory for testing ‘security’ technologies, both as a research and marketing advantage for global sales. This partnership has been abundantly financed by the EU framework programme on ‘Security Challenges’. As in many such cases of military design and intent, the phrase ‘dual use’ would be an understatement.

Such institutional linkages and usages are exemplified by the University of Manchester’s graphene research; its results are held by a commercial spin-out, in turn licenced to the Israeli arms industry. The BDS campaign is a potential threat to academic complicity of this kind. Perhaps not coincidentally, in 2017 the University systematically deployed the IHRA criteria against the activities of its student Palestine Society. This example highlights how the ‘antisemitism’ intimidation campaign protects the material interests of a UK-Israel partnership.

‘Community cohesion’ as a shield and pretext

Beyond universities, the government has sought to protect the UK-Israel partnership from attempts by Local Authorities to implement boycott or divestment policies. As the government argued in 2016, such local boycotts ‘can damage integration and community cohesion within the United Kingdom, hinder Britain’s export trade, and harm foreign relations to the detriment of Britain’s economic and international security’. Although such ‘damage’ is relevant to many issues and investments, the government policy sought especially to suppress the pro-Palestine BDS campaign.

For this purpose, ‘community cohesion’ means protecting the sensibilities of ‘the Jewish community’, presumed to be homogeneously pro-Israel, while disregarding or marginalising all other Jews. This agenda promotes a double exceptionalism. Amongst the various forms of race hatred, only antisemitism is conflated with a political identity, in fact shared by only some of the relevant ‘community’. Uniquely this serves to equate ‘offensive’ comments with racist ones, in order to censor or even discipline such comments, while separating antisemitism from racism in general.

What drives this agenda? A deeper explanation is suggested by an article by the SOAS academic Sai Englert (2018): ‘Jewish communities in Britain are being directly mobilised as a shield, behind which the government can hide to defend its own trade and international-policy choices, while also undermining political freedoms in the UK.’ This state-led agenda extends a long history of racializing colonial peoples abroad and ethnic minorities in the UK. A century ago, Jews were demonised as a danger to Britain’s Christian culture. Indeed, before and during the Nazi regime, many Jewish refugees were blocked by Western states.

However, the dominant narrative has since turned Jews into a vulnerable group helping to protect Israel and thus Western civilisation. When Western states commemorate the Holocaust, such events become a tool for claims to oppose racism and protect Jews from antisemitism today, while disguising the state’s institutional racism against other minority groups. (This pervasive role has analogies with state philosemitism in France, likewise constructing and instrumentalising ‘the Jewish community’; see the 2015 article by Houria Bouteldja).

As Englert further argues, ‘Jews can then become part of a Western hegemonic culture, which has recently discovered itself to be Judeo-Christian only a few decades after the Nazi genocide, on the condition that their history becomes a pillar of the state’s official history, rather than a boulder to bring it tumbling down.’ The Jew is reconstructed as defending the West’s values in the face of barbarism. This essentialisation paints Jews in a seemingly positive light. Yet ‘the underlying logic is a top-down structuring of Jewish identification by the Western state’. Under the banner of Zionism, Jews are mobilised against negatively racialised communities and critics of the state’s foreign policy (says Englert).

In this way the state narrative has been readily extended to demonise anti-Zionist forces as the main antisemitic threat, contrary to statistical analyses blaming mainly the Far Right. This state agenda becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: many Jews become frightened, so feel less secure and identify more strongly with Israel. In reality, in the general rise of overt racism since the 2016 Brexit referendum, other minority groups have been the main targets of physical attack. Yet nearly one-third of British Jews are considering emigrating because of safety fears (The Guardian, 10.12.2018). The pro-Israel Jewish press even warned that a Corbyn-led government would ‘pose an existential threat to Jewish life in this country’ (Jewish Chronicle, 25.07.2018). It became thinkable that their readers would respond with fear – rather than ridicule. In effect, the state-led agenda has served to entrap Jews, politically and psychologically.

Strategic implications

As this analysis has argued, the British state displaces its pro-Israel commitments onto ‘the Jewish community’, constructed as Zionist and thus vulnerable to antisemitism. This provides a convenient shield for the state’s partnership with the Zionist colonisation project. This agenda aggravates societal divisions – frightening Jews and dividing them from each other, while also separating them from the Left and Muslims.

[reference: Labour adopts IHRA antisemitism definition in full]

This analysis suggests the need for a counter-strategy encompassing several actions:

- Attack the state construction of the Jew-as-Zionist for pressing Jews into such an identity, conflating antisemitism with mere ‘offence’, shielding the state’s pro-Israel commitments, and disguising its power as the Israel lobby’s power.

- Target real antisemitic conduct (especially of the far Right) within a general struggle against racism in all its forms, in creative ways which can overcome societal divisions and fears.

- Defend those who are falsely accused of antisemitism or are accused simply of ‘offensive comments’.

- Oppose their persecution or censorship within disciplinary procedures of political parties, Local Authorities, universities, etc.

- Explain why the Zionist colonisation project has always been ‘a racist endeavour’ (key taboo in the IHRA examples), thus clarifying the source of the Israel-Palestine conflict.

- Extend the BDS campaign against institutions complicit with the Zionist apartheid settler-colonial regime.

How to combine those actions in effective ways? This ambitious task warrants more strategic discussion.

Major References

Bouteldja, H. 2015. State racism(s) and philosemitism or how to politicize the issue of antiracism in France?

Englert, S. 2018. Judaism, Zionism, and the Nazi genocide: Jewish identity formation in the West between assimilation and rejection, Historical Materialism 26(2), Identity Politics special issue.

Free Speech on Israel. 2017. What antisemitism is – and isn’t,

https://freespeechonisrael.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/IHRA-definition-antisemitism-briefing-2.pdf

Jewish Voice for Labour & Free Speech on Israel. 2018. What is – and what is not antisemitic misconduct, https://www.jewishvoiceforlabour.org.uk/app/uploads/2018/09/DeclarationOnAntisemiticMisconduct-1.pdf

Levidow, L. 2017. UK government defines antisemitism to suppress Palestine solidarity events,

BRICUP Newsletter 108, March 2017,

http://www.bricup.org.uk/documents/archive/BRICUPNewsletter108.pdf

Rosenhead, J. 2018. The definition that never was, BRICUP Newsletter 117, January 2018,

http://www.bricup.org.uk/documents/archive/BRICUPNewsletter117.pdf