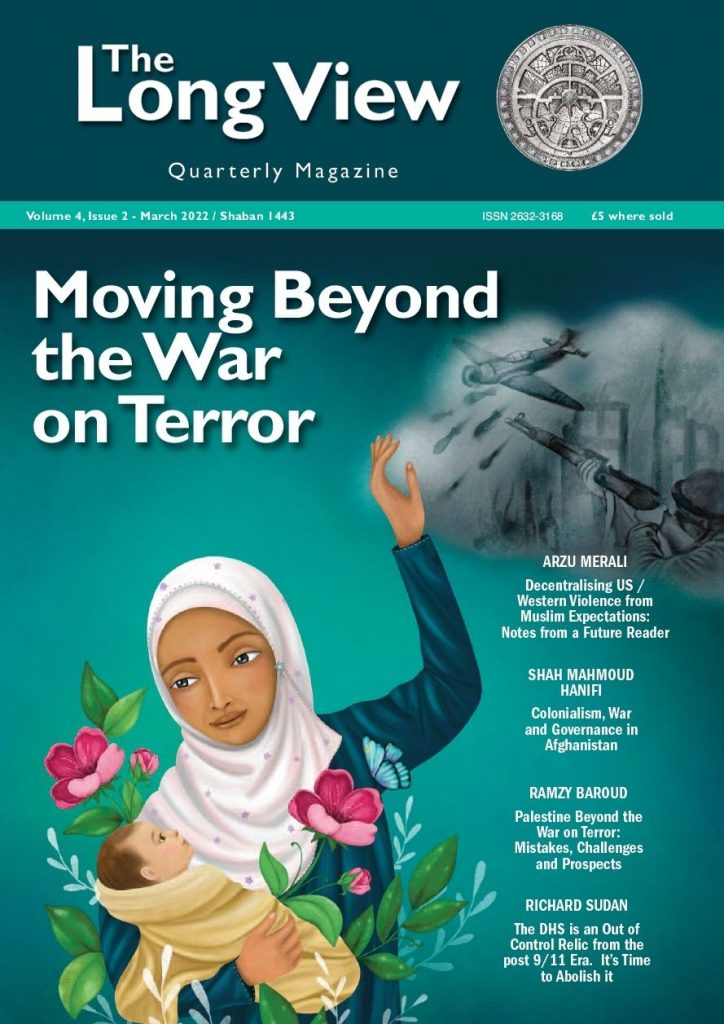

Moving Beyond the War on Terror.

Volume 4 – Issue 2 – March 2022 / Shaban 1443

Editorial

There is a tendency or temptation to view September 11, 2001 as a watershed moment in international relations. It defers to the narrative woven by politicians to legitimise the subsequent “war on terror” by seeing the deployment of unbridled force, lawful or otherwise, as a necessary tool to preserve a putative rules-based order. Even the unquestioning ease with which the abbreviation 911 and the phrase “war on terror” have slipped into the popular vocabulary and consciousness speaks to the ability of hegemonistic powers to shape discourse as a means of legitimating their abuses.

Yet scratch beneath the surface and it quickly becomes apparent that there was nothing defining about it. It marked no departure from the projection of colonial power at home or abroad. Despite oft-quoted cliches, neither the rules of the game nor the world changed on that day. The domestic and foreign policies of global powers continued along the same well-hewn channel, the only difference being that the gloves came off and the mask was peeled back. A retaliatory attack on a global power for its overseas excesses became a pretext for governments everywhere to brazenly double down on anyone that dared oppose their injustices.

The crushing force and scale of the “war on terror” has had impact for Muslims in every imaginable sphere of life. It unleashed a tsunami of Islamophobia that served as a prerequisite to selling the atrocities carried out in its name. It has sought to re-educate believers in their own religion, to save Muslims from themselves (read rewriting Islam) in order to ensure political consent. Without a “war on terror”, it is doubtful Britain would have established the Prevent programme, designed to produce a politically emasculated, compliant Muslim population. Nor is it likely that China would have set up concentration camps to scale up its erasure of the Uighurs’ religion and culture, nor that anti-Muslim Hindu supremacy would have spread so much in India. The casting of Muslims as the world’s bogey men has made them targets of discrimination, set back liberation and civil rights movements, and set off a rampant cancel culture that seeks to blot out their very existence as political actors.

Reeling under such blows, bitterly divided and facing a seemingly irretrievable imbalance of power, Muslims have grappled with the question of what should be our response. In our lead article, Arzu Merali highlights the fact that the war on terror has its origins in the same US playbook that gave us the “war on drugs” in the 1970s and the war against various movements and causes before that. She castigates the community for not heeding their lessons and adopting a defensive posture.

In order to rethink and plan our future outside the boxes into which we have been forced, Merali argues that Muslims need to come up with alternative models that are not merely poor imitations of neo-liberal democracy or socialism but which are rooted in values which offer genuine hope for a better future. We need to reject outright the ‘us versus them’ divide and rule rhetoric employed to dress up a war whose motives are more about power, resources and our own subjugation than any professed altruism.

The first military casualty of the last twenty years was Afghanistan. Known to be the hideout of the alleged perpetrators of the attack on the US it became the locus of another US war and occupation. Having overthrown the ruling Taliban and installed a client regime the US would stay for 20 years in a move viewed by Shah Mahmoud Hanifi as falling on the same colonial continuum as the British and then Russian invasions in the 19th and 20th centuries. Hanifi shows how Afghanistan became a dark ops site and military testing ground where the US indulged in systematic atrocities. Critically, it cemented ethnic rivalries and made ethnicity the currency of politics, locking in conflict into the political system. With international sanctions now starving its people and squeezing its economy, Afghanistan faces a mammoth struggle to undo the legacy of successive colonial occupations.

The ongoing war in Ukraine has once again exposed the double standards governing international politics. The rush to sanction and isolate Russia is a stark contrast to the complicity of nations in the subjugation of Palestine. In our third piece, Ramzy Baroud looks at the devastating impact on the Palestinian struggle, particularly in how it is popularly viewed. Barely had the dust settled on the site of obliterated World Trade Center than Israel launched a comprehensive media campaign conflating the freedom fight and so-called ‘Islamic terror’, presenting itself as an ally in the “new” global war. Meanwhile, Palestinian leadership fell into the trap of assimilating itself into the prevailing narratives, even when clearly detrimental to the long term aims of the liberation struggle. Palestinians in parts of the diaspora fared little better. As US forces invaded Iraq, the Palestinian community there faced reprisals from resurgent with impacted forces who perceived them as being com- plicit in the erstwhile strongman’s persecu- tion of the Shia community.

Atrocities committed in the name of freedom and democracy were also answered with reprisal attacks on western soil, vindicating (and justifying the acceleration of) governments’ erosion of civil liberties. In the US, the centrepiece of this was establishment of the Department for Homeland Security, one of the largest federal agencies, boasting close to a quarter of a million employees. In the final piece in this issue, Richard Sudan argues that the DHS has been an unmitigated disaster for Americans from the way it handled the response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005 to its spying on civil rights activists, Muslims and blacks, its mistreatment of migrants and its abject failure to prevent the rise of white supremacist groups that ultimately led to the storming of Congressional buildings in Washington in 2021.

All the contributors to this issue challenge not just the conventional thinking of the so-called war on terror, but also those who have been marginalised and oppressed by it. Finding ways out of the various sectarianisms – ethnic, religious, political – is critical. By continuing to see the world in the partisan way fashioned by colonial powers, old and new, we are simply perpetrating violence on ourselves. Let’s rewrite the script and move beyond the “war on terror”.