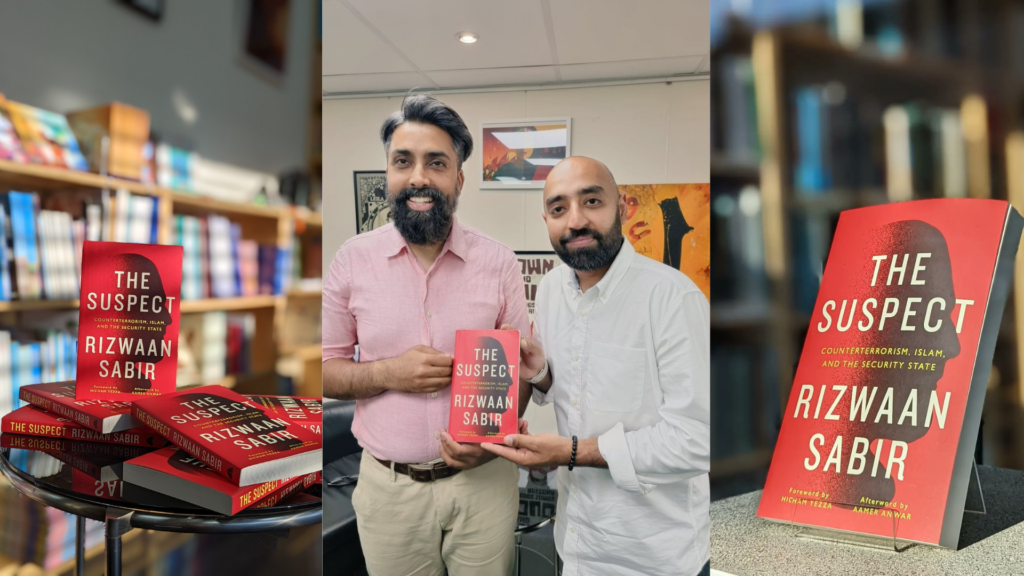

IHRC hosted an author evening with Dr Rizwaan Sabir on Friday, 12 August, to discuss his book, The Suspect: Counterterrorism, Islam and the Security State. Dr Sabir is a lecturer in Criminology at Liverpool John Moores University.

The Suspect focuses mainly on Dr Sabir’s personal experiences with the National Security State, noting ‘what led to his arrest for suspected terrorism, his time in detention, and the surveillance he was subjected to on release from custody including stop and search at the roadside, detentions at the border, monitoring by police and government departments and an attempt by the UK military to recruit him in to their psychological warfare unit’.

Purchase The Suspect: Counterterrorism, Islam and the National Security State from the IHRC bookshop here

WATCH THE FULL EVENT HERE:

The event was chaired by Talha Ahsan, host of the Abbasid History Podcast. Talha started the event by humorously showing Dr Sabir a picture of when they last met, followed by Dr Sabir reading a brief extract from his book:

“By the time I reached the top of the stairs of my parents’ home to see what the shouting was, the front door had already been forced open. Three policemen wearing white shirts with collar badges showing their ID numbers, black ties, black trousers, and shiny black shoes were stood in the hallway. They wore blank expressions on their face. The morning sun was beaming through the broken door with the smoke glass panels that surrounded it. On hitting the oak flooring, the sun created a blinding reflection. One of the policemen was watching me, stood at the top of the staircase as I looked at him with a mix of fear and confusion. The other two walked into the kitchen and were now out of sight. One of the officers remained in the hallway and continued staring. He raised a blue piece of paper in my direction, his way of inviting me downstairs but without moving I already knew what the sheet of paper was: it was a warrant for my arrest on suspicion of being a terrorist and laid out the legal grounds on which the police were going to search my home. Before I could do or say anything, I found myself sat in a chair. In the semi-centre of a large room which had extremely bright ceiling lights and white walls which seemed to go on forever. Around 10 police officers who stood around me talking over one another filled the room. I silently sat there trying to decipher what they were saying but to no avail.”

After reading the extract, Talha explained that before they go into the issues raised in the book, he wanted to ask about the background and upbringing of Dr Sabir.

Talha: What was it like in Nottingham as a Muslim?

Dr Sabir: Nottingham was predominantly working class and it is quite a mixed community. It has a history of communities that have migrated from the West Indies, South Asia, predominantly Pakistan, Azad, Kashmir, with a small number of Bengali families and a fair few Sikh families or Indian-Sikh families. And families of white working-class communities but generally it is quite diverse. It is not a bad city; there’s enough going on to keep the ordinary person occupied and busy. Relations between communities have generally been very good and I have been to a series of very mixed schools in terms of ethnicity. I had friends from various cultural backgrounds and now increasingly, as the years have passed, arrival of people from Eastern Europe, Iraq, and Afghanistan [as well] because obviously of world politics and geopolitics. It is evolved but generally the city was always good to me. The people were quite mixed which obviously helps with diversifying your mind.

Talha: Have you had any kind of fresh insight or subsequently after writing this that you missed on any important details?

Dr Sabir: Yes, there is one thing is that really bugs me because I have to repeat this to a number of people and it’s a very minor thing, but I wish I had written a sentence to say, “if you are not interested in understanding how this story relates to the broader global conflict, war, the dirty war, more known as the war on terror, you might want to skip to chapter 26.”

A lot of people are interested in the story rather than the broader context, so I just wish I had written that. It is also just me being slightly facetious but also more importantly and on a serious note, there were a series of stops that were executed by the police that get no real mention in this book because they are not directly relevant or related. So, the levels of state violence and interests that I was experiencing is a lot higher than what I have accounted for in the book because there were no direct parallels being stopped and searched and detained in a Section 60 stop and search zone to the arrest for suspected terrorism.

Talha: What is Section 60?

Dr Sabir: Section 60 is a zone that is designated by a police force to be an area where the police can execute a stop and search without reasonable suspicion that you are involved in a crime. Merely being present within a section 60 zone is grounds for you to be stopped and searched if the police desire. When I was in Nottingham, in an area called St Annes, which is predominantly Afro-Caribbean, I was passing through and I was stopped by armed police officers who were dressed like SWAT, essentially helmets, goggles, police dogs and they were everywhere. There were helicopters flying over the area. My friend who was accompanying me and myself, were stopped and then we had the car searched. We were questioned and when I challenged the officer and probed his authority, it led to more problems for us, with threats of arrest, having the car seized and so on and so forth. That incident was not directly related to the arrest for suspected terrorism and so it is not mentioned in the book.

Talha: I think you mentioned that in your book because you talk about something that happened with your cousin but what’s interesting is that there’s a lot that happened after that incident but now you are saying that you left things out?

Dr Sabir: I think in hindsight, it’s useful to have included that because it showed you that it’s not only being a person of interest for suspected terrorism, wrongly of course, that leads you to be a marked person. But just when you’re a person of colour going about your ordinary life, in a city like Nottingham, or Liverpool, Manchester, or Birmingham where there are a sizeable, racialized population, state violence comes and knocks on your door when you’re just crossing an area that’s just been declared a section 60 zone, for example. So, state violence does not just come knocking on your door when you are accused of being a suspected terrorist, but they actually come just by virtue of the fact that you are a racialized minority and I think there’s something to be said in that.

Perhaps it could have been relatable or felt more empathetically by ordinary readers who probably have more in counters with stop and search for drugs or carrying a concealed weapon or a section 60 zone like they do for terrorism. One of the additions that I could have included were incidents which were more relatable, but I was on a word limit, so I couldn’t include everything. But maybe I could consider that for the second edition if it ever goes to that.

Talha: You mentioned your experience in Nottingham but then you mention these kinds of incidents, they don’t marry…

Dr Sabir: Nottingham is home – I was born and raised there, my schooling was there, my family and friends are there, my Friends are there. Nottingham became a difficult terrain for a long time and there were memories and triggers all around the city, but I’ve passed the prison where I was held probably daily, for most of my life after 2008. You become desensitised to those same spaces but I think there was also a conscious decision to not allow those memories to be tarred by state violence; there was a proactive effort to return to campus and to spend time there because I was not going to allow the state to take away the serenity and the joy that I felt at the University of Nottingham’s very picturesque campus.

In the same way that was not going to allow the city where I was born and raised and is my comfort zone to be tarred by the experience of state violence, for being arrested for suspected terrorism, or stopped and searched, or detained, or questioned under the roadside for terrorism or whatever it may be. Instances that I of course describe in the book. So, it was partially an unconscious but mostly a conscious decision to not allow that experience and familiarity to be tarred.

Talha continued asking a few more questions surrounding the various themes mentioned in the book, followed by a Q&A with the audience. This is a recommended event and book for those interested around the issues of extremism, prevent, the national security state, racism and the Muslim community.