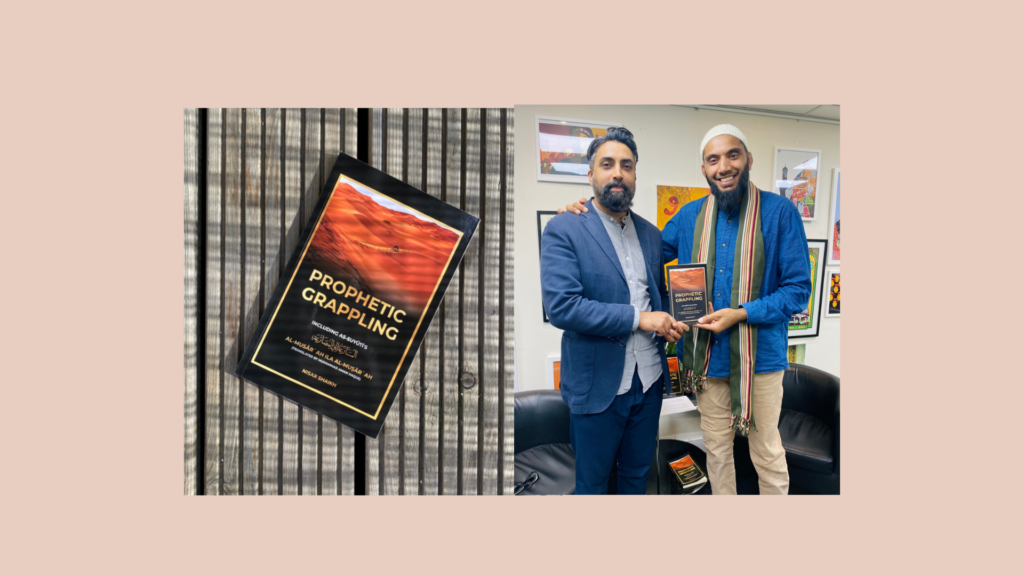

IHRC held an author evening on Friday, 23 September 20233, with Ustadh Nisar Shaikh, to discuss his book Prophetic Grappling.

Purchase Prophetic Grappling from the IHRC Booshop.

WATCH THE AUTHOR EVENING HERE:

Nisar Ahmed Shaikh is an avid grappler having trained extensively in Jiu-jitsu and cross trained in freestyle and Greco-style Wrestling, Judo and Sambo. He holds a black belt in Jiu-jitsu under the Carlson Gracie Team London. His passion for the grappling arts has taken him abroad, seeking out instruction from some of the best grapplers in the world, visiting Brazil, Japan, USA and Canada. He is a deeply passionate and active teacher with over fifteen years’ experience, instructing all levels, from professional MMA fighters to young children. He currently serves as a Muslim Chaplain at Royal Holloway University in London, where he lives with his family.

This event was chaired by Talha Ahsan, host of the Abbasid History Podcast, sponsored by IHRC. The conversation has been edited for better readability.

Talha introduced the author and the event by explaining the format of the book; the first part is on the history of grappling, the second part is a translation and rendition of essays and summaries of Shaykh Mohammad’s work on grappling, and lastly, the third part is a translation of a collection of 18 commentaries by Imam As-Sayuti.

Talha: Tell me about your journey into martial arts

Nisar Shaikh: My journey in training in martial arts started at university. As a young person I had a lot of bad experiences in terms of racism in the area I lived in. It is slowly changing alhamdulilah, but there was a lot of bullying and fights. It moulded the way I saw the world and how I understood combat. As I rolled into late teens and 20s, and I went university, and it was very clear to me that all that was out there in terms of martial arts training, it was somewhat conceptual. It wasn’t practical. My experiences of fighting or getting beaten up were very real and scary so then at university, I came across ‘Brazilian Jiu Jitsu London’; my instructor then is still my instructor today. He was a brown belt at the time, from Brazil and was teaching in Earl’s Court. I remember going in there, smelly, sweaty matting, not very pleasant, rough and ready and that’s how I started.

Martial arts is immediately applicable – from day one, whatever you learn you’ll be able to apply immediately, much like boxing, Muay Thai, jiu jitsu, wrestling – these are all very pragmatic martial arts that you can apply. That was my journey into the grappling arts, and as I progressed over many, many years, I also competed in my early years. I’m now in my 40s, and I don’t compete as much. I have a few health conditions, trigeminal neuralgia, so stabbing pain in my face; if I freeze, [it is because] there is pain in my face and it eventually passes.

Jiu jitsu is primarily ground grappling form, and when you go to tournaments and compete, you start standing. I then ventured into judo and free style wrestling. I’ve been to Brazil and Japan for extended periods of time to pursue a greater understanding of the grappling martial arts. Later I had the honour of being given the black belt in 2014.

Jiu jitsu is quite a tough art in the way that people progress through it; it typically takes around 10 years to get a black belt, but even then, the black belt is not the end goal. It is a great achievement, and it certainly was for me, but it is a continual journey.

Talha shared some of the praises Nisar Shaikh received, including Jordanian Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad, former UFC fighter from Liverpool Mario ‘Sukata’ Neto, and Habib Kazim from Yemen.

Talha: Let’s talk about the history of grappling globally and specifically in the Islamic civilisation – what did you find during your research?

Nisar Shaikh: I am still a student of the Arabic language, so I did not have access to the primary resources, but my teachers and scholars were very generous with their time, and they would translate a lot of historical resources. The seerah of the Prophet (saw), Martin Lings’ work, and a few other translations from different people, were very useful in piecing together the history of grappling. There are lot of other works and biographies, of Khalid ibn Waleed, Imam Ali, and other sahabas, Imam Ali, and I gathered these works together.

A lot of my feelings towards how Arab men would wrestle and their appetite for wrestling in that area came from discussions with Arabs. When we’d go for umrah, and upon visiting and meeting scholars, I’d ask questions and strike conversations [about grappling], and they’d look at my ears and comment on my ears. It was nice to hear their thoughts. I was in Turkey for a conference on Palestine some years ago, and a shaykh from Lebanon looked at me and said, “you either do boxing or ‘sarra’”. I didn’t know what that meant, so he said “wrestling”, and I said smiled and said “yes, I do a type of wrestling: grappling”, and he spoke very fondly and passionately about the wrestling in Arab culture. A lot of my understanding came from [those types of conversations].

I also grew my understanding by read some of the works which are in English and accessible. Through reading in between the lines and amalgamating what I understood about Arab culture, and by speaking to people, that is where I got my understandings from.

The antiquity where there was no modern policing, armies, or other such institutions, [grappling was a] way that people would look to self-defence and self-preservation. You simply could not be sedentary; everybody was very physical, hardy and capable – men and women, unlike modern living.

It was a labour of love. As a grappler, and insha Allah as someone who has a love for Prophet Muhammad (saw), I always think about where he would wrestle. My teachers would tell me, he (saw) was there in the rawdah, and in Makkah, and other locations were certain events took place. There is still a lot of work to be done; it would be nice to do a critical deep dive into the ahadith, especially for people who have the appetite for critical analysis. That may happen in another edition.

Talha (referring to page 15 in the book): With the Prophet’s (saw) mosque and the role combat sports had in his life and in the lives of the companions in these sacred areas… how do you think we could reintroduce this kind of vitality into our lives?

Nisar Shaikh: This is an important question… it starts with us; if we feel that this is not part of our Islamic heritage, if we think it is separate to that, and just a good thing to have, like going to the gym, then we are not going to embrace it. It is clear that it is in our literature and thus, we need to embrace it. People have a preference to the prophetic practice, not discount the other practices that are there. The physical practices of the Prophet (saw) is not only beneficial physically, but also has a spiritual dimension – embracing this would really help.

I learnt primarily from non-Muslims, and I am deeply grateful for them, but there are many, very capable Muslim instructors out there. Having vitality and strength revives people’s their faith. I know many people, Muslim by name perhaps but not so much in practice, that when they find out the Prophet (saw) grappled, they felt an immediate connection to him.

We were reading some commentary in the Shama’il of Imam Al-Tirmidhi; it was said the handle of the sword of the Prophet (saw) was so worn down due to frequency of use… he (saw) was a man of the spear. We know narrations of archery and horse-riding as well – these are really beautiful arts we could all do. It takes initiative in the part of mosques and organisations, and willingness on the part of the community.

Talha: You mention female companions who had a warrior aspect to them… Tell us about these figures and anyone that impacted you in particular

Nisar Shaikh: I feel very strongly about womenfolk learning the martial arts, for self-defence reasons, but also for confidence. I came across man narrations of women, like Safiyya bint Abd al-Muttalib and Nusaybah Bint Ka’ab, Allah be pleased with all of them.

One of my teachers, Shaykh Akram Nadwi, wrote a monumental work on female scholars, and the women were certainly good in the academic side of things. I asked Shaykh Akram if women excelled in other areas, and he mentioned that women very physically strong, and some were stronger than men. How could a woman take a place on the battlefield having not trained? It was clear they were very capable women, and it shows a side of the Prophet (saw) that people are simply not aware of or don’t want to believe because of their cultural understanding of Islam. The Prophet (saw) engaged womenfolk in a very serious way and had a lot of praise for the women.

Talha and Nisar also discussed the importance of trying your best in any prophetic practice, why men and women should do sports, the physical and spiritual preservations and confidence of engaging in sports, masculinity, tarbiyah, the permissibility of being struck in the face, and how women can get started in martial arts.