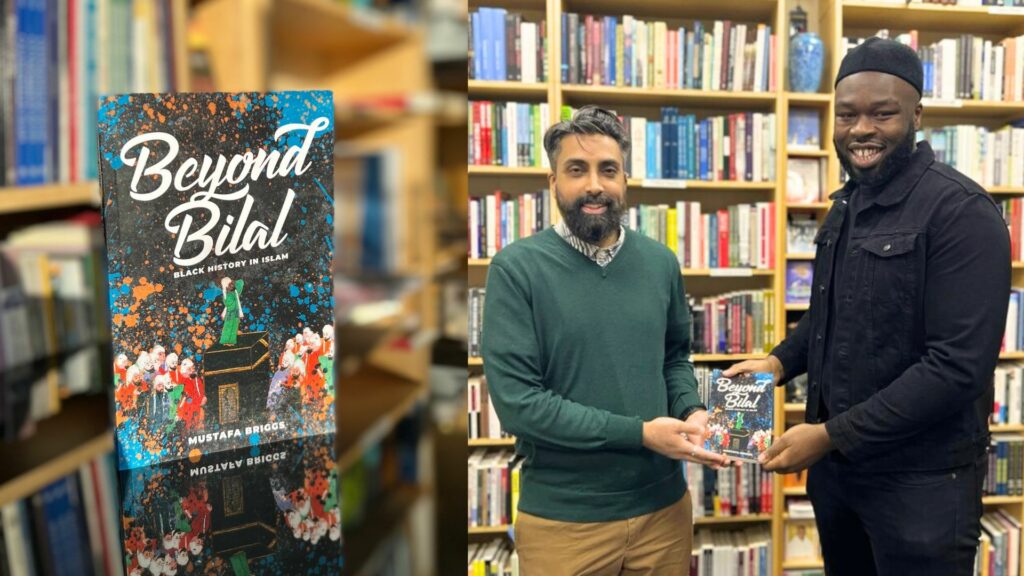

IHRC were pleased to host an author evening with Ustadh Mustafa Briggs in February 2023 at the IHRC Bookshop. This event was hosted by Talha Ahsan. Purchase Beyond Bilal here.

WATCH THE AUTHOR EVENING:

The conversation below has been edited for better readability.

Talha commenced the event with an introduction to Ustadh Mustafa Briggs and his book, and asked about his visiting Gambia and meeting the President of Gambia, Adama Barrow.

Talha: there are figures in the Quran that are described phenotypically as Black, which might surprise some people – could you give us an overview on what that might be?

Mustafa: the book is a combination of a few lectures; the lecture series began with explaining Black history in the Quran and Black history around the Prophet (pbuh), and the history of Islam in West Africa. That was the original Beyond Bilal series. After that I did an American tour with that series and through discovering the rich histories of Islam in the Americas, I wanted to expose that to the UK because we usually think of blackness and Islam as starting with Malcolm X and we don’t really know anything that happened before that. The first place I delivered the lectures on Islam in America was at the London School of Economics as part of their public lecture series. I had a third lecture on female scholarship in West Africa in the Islamic tradition.

The first section talks about Black figures and history in the Quran. Luqman is a prophet mentioned in the Qur’an. Usually when I give the presentations, they are interactive and I ask the crowd questions and I respond to their answers to highlight the way in which we have been trained to think, interpret history and look at historical figures. For example, ‘can you name any Black figures in the Qur’an?’

Today, if we think about Black people, there are groups of people who are phenotypically described as being Black people regardless of their from East or West Africa or wherever. These are people that if you look a certain way and enter into certain communities and spaces, you will be racialised as being Black and that comes with prejudices and discriminations and anti-Blackness, which is a global phenomenon as we see ourselves in a Eurocentric monoculture that is established in white supremacy.

For people on the other end of the spectrum, people who look like me, we grow up experiencing these things and I wanted to flip it on people in terms of the way history has been whitewashed. There are many figures in the Qur’an that if they were alive today, they would be racialised as being Black because their physical descriptions are exactly like the victims of anti-Blackness today.

In Islamic history in general, Luqman’s Blackness is always linked with slavehood and it is the same kind of language when we speak of Sayyidina Bilal. Even though he was free within a year of becoming Muslim, in Muhammad by Martin Lings for example, he is constantly talked about as a slave because there is a subliminal link between Blackness and slavehood. Other figures, such as Yusuf (as), they were all formerly slaves but nobody ever refers to them as being slaves or links their essence and character to slave hood.

Talha also asked about anti-blackness among Muslim communities in the UK, and the notion that Marxism and identity politics attempt to push forth a sinister agenda that we should be sceptical about this rhetoric. Talha: One of the gaps I noticed in the book is that East Africa is not mentioned and UK history. For example, you can find this rhetoric among diaspora Somali community that they are not part of this Blackness movement, it is part of a decolonial marxist agenda and it corrupts young minds. What are your thoughts on these critiques?

Mustafa: the rhetoric around anti-blackness being a marxist agenda is interesting. If we look at islamic history before Marxism even existed, people were having these conversations in our scholarship. In the second chapter, I reference two books and there are other books referenced in Jonathan Brown’s book, Islam & Blackness, books written by scholars in medieval Arab Muslim countries, such as Jalaludin Sayuti, that were writing books tackling anti-Blackness in the Muslim community. Us discussing anti-Blackness now is not a modern issue and it cannot be a Marxist agenda because before Karl Marx was even born, there were over 15 books written tackling ant-Blackness in the Muslim community from a Qur’anic and Sunnah perspective. Anything that is something helps us in positivity, I cannot see it as a sinister thing. It is not sinister to say black people should not be discriminated against.

There’s the way in which we see ourselves and there’s the way society sees us. The context of being Black for example, I have met Africans who have said, ‘I didn’t know I was Black until I went to the united states or moved to the UK’. Because in Africa, even before colonisation, we didn’t have this way of thinking of black and white, the thinking was more like we belong to this tribe, or this ethnicity, or this kingdom. Even the nation states we describes ourselves as being from, did not exist 200 years ago. Even if you do not identify yourself as black, you go to different communities or certain places, you will be racialised as black, whether you like it or not. There are people who might identify as Yemeni or Arab and they enter wider Arab races, people look at them call them abeed, because they are being racist towards them. It is not about how you identify yourself, it is about how society identifies you.

Ustadh Mustafa also answered questions from the audience and other topics discussed during this event include studying the Islamic scholarship in west Africa, the descriptions of the Ahlul Bayt, the transatlantic slave trade, female Islamic scholarship, Islam in the US and in modern history, Black empowerment movements, and more.