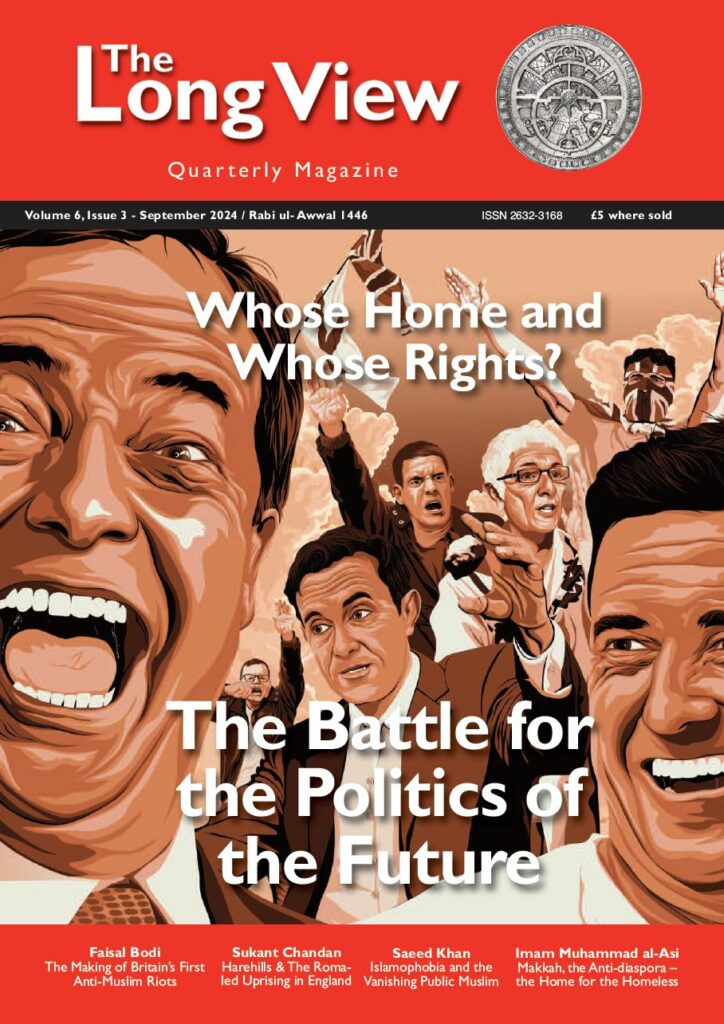

Whose Home and Whose Rights?

Volume 6 – Issue 3 – September 2024 / Rabi ul- Awwal 1446

Editorial

This latest issue of the Long View is focused very heavily on recent events in the United Kingdom, the role of Islamophobia in those events and the geopolitical networks and systems that have been exposed as a result. For the benefit of future readers and those not based in Western Europe, the United Kingdom experienced extreme unprecedented racist mobilisations against Muslims, migrants and asylum seekers in early August 2024. This included arson attacks on hotels housing refugees, physical attacks on mosques and violence against individuals perceived to be in any of these groups.

In our first piece, Faisal Bodi dissects the events with a long background into how we have ended up in the current situation. Drawing on battles between antiracist and both the state and street level thuggery over the decades, Bodi outlines the developing environment of hate that has led to the recent riots. En route he unpacks the narratives that have become the ‘truths’ that those incited to riot have internalised: the idea that minoritized and racialised communities have been in receipt of state support and help above and beyond that received by their counterparts; that Muslims in particular have been targeting young white girls and children for sexual exploitation; that the social fabric and nature of the UK is under threat and imminent danger from illegal immigrants travelling by boat from continental Europe, Muslim entryists at every level of the social and political system, and pro-Palestinian activists and protestors. These narratives have not sprung up organically from the streets or been promulgated by fringe far-right groups (only), they have found succour and have been, in the main, (re)produced by mainstream actors.

Looking at the reality on the ground, Bodi finds minoritized communities hitherto politically under siege, now literally so, as pogrom style violence found expression on the streets this summer. Referencing his previous work on previous riots that gripped norther English towns in the summer of 2001, he argues that the demonisation of those rioters by the state and a failure to take their grievances seriously (they were largely South Asian heritage Muslims protesting social and police racism) is a key moment in the journey to where we are today. That demonisation is very much part of the discourse of international Islamophobia networks, aligned often with Zionist and white supremacist groups, and increasingly mainstreamed across Westernised settings.

This demonisation, whilst highly apparent against Muslims affects other minoritized groups too. Towards the end of July, a so-called riot also occurred in the Harehills area of Leeds. This time however, it related to the grievances of the Roma community who erupted in protest at the continued removal (with what appears to have been unwarranted police force) of Roma children from their families into the care of the state. Sukant Chandan, in our second essay, argues that this incident has not been recognised by other marginalised groups and the wider white working-class as it should have been: a case which required support and solidarity from other oppressed groups. Both Chandan and Bodi’s prognosis is bleak – British society and state are captured by narratives, policies and laws which are nativist, brutal and with terrifying precedent.

The erasure of Muslims from civil society and political spaces is the theme of this year’s IHRC and SACC Islamophobia conference. Saeed A. Khan’s essay covers the talking points for the event. With every passing year, and in acceleration since October 2023, Westernised spaces but also countries such as India have introduced laws and policies that shrink political spaces and target Muslims. A combination of poor strategy and an environment of fear and hatred has kept Muslim civil society at a permanent disadvantage. Nevertheless, whatever pushback that has come from these sectors has found the state in these contexts scurrying in disarray – a pointer to the (albeit painful in consequences) possibilities of challenges to racist and oppressive structures and governments. Khan’s piece looks at the US, UK, Germany, Australia and India and provides an overview of how Islamophobic and anti-Palestinian networks have thrived.

Our last essay is based on one of Imam Muhammad al-Asi’s presentations at the Decolonial Muslim Studies Summer School, held in Granada in June 2024. In it, he propounds the idea that from a Qur’anic perspective Makkah has been decreed a home for the homeless. At a time when religious and cultural difference, as well as migration, have become markers of inferiority and or threat, this type of dynamic thinking can get Muslims and those with a view to a future of different possibilities to reimagine ‘homelessness’ and ‘belonging’. If the holiest land in the Islamic faith is meant to be a home for all those needing a home and a place to belong, what does that mean for our everyday practices of faith and politics? The possibilities are enormous and the prognosis possibly spectacular. Let’s start reimagining the future this way.