IHRC, SACC and DIN held the 8th annual Islamophobia Conference over the weekend of 11 and 12 December, to address the questions posed by Muslim participation in civic and political life in the so-called ‘West,’ including countries like the UK, the US, the European Union, Australia and Canada**. Is it possible to tackle racism, Islamophobia and other injustices by working in the system, or must there be complete or near total refusal to work with governmental and other institutions of the state? What are the dilemmas Muslims face and what lessons can be learned from contemporary movements from various communities.

A written report follows the videos of the session.

Watch Day 1 (sessions 1 & 2) of the Islamophobia Conference 2021 here:

Watch Day 2 (sessions 3 & 4) of the Islamophobia Conference 2021 here:

For Muslims, the theological, academic, communal and strategic considerations are complex and often convoluted, intertwined, and currently creating fissures within the Islamicate that are either exploited by external forces or at the least, making any sense of Muslim pluralism, let alone unity, highly elusive. A conversation that assesses all of these factors, their parameters and offering strategies moving forward is an essential intervention for Muslim communities whose agency and viability in the societies where they reside is in constant question by the establishment of and in the ‘West.’

**Aside from the type of regions mentioned above, there are those where Muslims reside as minority communities, oftentimes as scapegoats for pre-existing social ruptures and as targets of discrimination. But these questions are not just for Muslims living in the ‘West’ as countries that are Muslim majority or have large Muslim populations bear the burden of being institutionally ‘Westernised.’ These nations, including Nigeria, India, Pakistan, South Africa, Malaysia and others, face the reality of asymmetric power dynamics with the ‘West’ as well as with those within their respective countries that are colonized and westernised from within. The scheduled panels will address the various issues that arise on the always timely question of how much engagement with the establishment of the ‘West’ and its vestigial forces is prudent, acceptable and necessary, if at all.

As explained by Saeed Khan, The Muslim world continues to reel under the continuing trauma that it has experienced, especially over the past century with the institutionalization of colonialism and its myriad systems of occupation and oppression. The legacy of these impositions, from without and from within, is exacerbated by a consistent record of military intervention that has wreaked havoc on Muslim societies in dozens of countries, unleashing generational trauma and devastation. The power imbalance between Muslim and so-called ‘Western’ countries, and between Muslim communities living in the so-called ‘West’ as minorities vis-à-vis the respective dominant societies, coupled with the constant pressures on these countries and communities alike by way of geopolitical impositions and Islamophobia, has spawned considerable soul searching within the Islamicate.

The question that consumes Muslims caught in these quagmires is one of engagement: should Muslims interact with the very establishment that may be responsible for their marginalization, discrimination, securitization and even incarceration. In other words, can Muslims work with the Western(ised) establishment? If so, are there conditions and what are they? If not, why not? Read the full article here.

Please read below a summary of each session.

Saturday, 11 December

Session 1: The Theological Case: Islam, Muslim Cultures and the Possibilities of Interaction

On the first day of the conference, the first session, entitled The Theological Case: Islam, Muslim Cultures and the Possibilities of Interaction, chaired by Seyfeddin Kara, the keynote speakers Dr Abdul Wahid and Shaykh Saeed Bahmanpour, discussed their papers.

Dr Abdul Wahid described the nature of our deen of Islam and how it is applied within and upon political realities. The main thing I would like to address: what do we mean by working with the Westernised establishments? In those areas where we engage or interact, is our position of a pragmatic way where we have a noble end or a justified end and the means we approach should be enough to do, or should we follow, for theological reasons, a principled approach, and not enter into pragmatic politics. If so, how is it possible to exert any influence? Finally, what are we engaging for? This question needs to be understood because otherwise we cannot move forward as a community.

The examples brought to justify engagement or interaction, Islam does not prohibit them all, we must go in with clear eyes and understand that even when you are seeking rights Islam was permitted you to take, we mustn’t fool ourselves that we are in this just society or world, where these establishments are indeed fair. We should be aware of the political waters we are swimming in. If you enter into those waters, you will get swept against very dangerous rocks and situations and sometimes Islam even prohibits you from entering into those waters.

What are we engaging for? The conference today is about Islamophobia, so are we going to engage just to defend our community? That is a noble cause in itself. When you observe many Muslims that engage, they have lost even that objective. It is almost as if engagement itself is their end, just to get recognition from the authorities and they celebrate that. I say our Islam is a complete way of life. Worship in Islam is not just confined to rituals, which is very important. It is [also] our politics, enjoining the good and forbidding evil, it is the economic way of life. Therefore, should it not be the goal that we start to work for something fundamentally better, in a principled way without compromise. If you are discussing the limits of engagements within the Shariah framework, then we can start to have a productive conversation about tactics.

Shaykh Saeed Bahmanpour began his discussion based on the incident called, Ḥilf al-Fuḍūl: the pact gives Muslims a precedent for their moral responsibility to protect the weak, speak for the speechless, establish groups of advocacy, and struggle for social rights in cooperation with other citizens regardless of their faith, and even if there are bigger issues that they disagree upon. means it is forbidden for a Muslim to engage in any activity which involves oppression, injustice, and transgression, whether that engagement is with Muslims or non-Muslims. As I said before, injustice and oppression are meta-religious anti-values. The Quran forbids engagement in actions involving such anti-values in different verses with different tones and expressions. “Do not be inclined towards the unjust lest the Fire should touch you,” “Do not be an advocate for the traitors,” “God enjoins justice and kindness and generosity towards relatives, and forbids indecency, wrong, and aggression. He advises you, so that you may take admonition,” and many other verses.

Thus, from an Islamic point of view, the answer to the question of engagement with western and westernized establishments depends on another question, namely, what type of establishment are western and westernized establishments. Certainly, when we talk about western establishments, we should not ignore the fact that these establishments are not monolithic and they differ from one country to another. At the first glance, we may classify them in two categories. Establishments which consider their national interests in intervention in other countries through corrupt, deceitful and violent means, and those countries which are not like that. However, with all their differences, when we look at NATO and the European Union, we see in the west a united front on global issues.

One may ask, have any of these trends and policies which are justified by the notion of ‘national interest’ changed in the west? Unfortunately, the west has turned the idea of ‘national interest’ to a despicable idea when it comes to foreign policy. It justifies anything and everything. By engaging in the establishment, can justice-seeking people influence any of these policies or will they be influenced by it? The answer is crystal clear: You would not become part of the establishment unless you are like the establishment, unless you accept their ethos, their logic and their practice.

After the presentations, the panellists, Amina Inloes (author and teacher The Islamic College in London) and Massoud Shadjareh (IHRC Chair), shared their views on the papers.

Dr Amina Inloes noted that most of the values mentioned are not limited to Muslims. Western dominance is relatively new and the situation has changed and evolved, therefore these discussions will be coming up again and may have to be approached in a different way. Our classical thought is based on Muslim as a primary identity, but now many Muslims are starting to think in different ways and adopting different ideas. Allah creates different people for different reasons, and not everyone is meant to engage in politics.

Massoud Shadjareh mentioned the Salman Rushdie affair and commented on the deliberate attempt to pacify Muslims. Shadjareh said, when Rushdie wrote his thing we didn’t have a large umbrella organisation, but almost the whole community were united in condemning the book and supporting the fatwa including non-practising, only two groups opposed it. We need a collective vision like at that time. Due to prevent and institutional Islamophobia, Muslims have lost the confidence to speak out.

There is a deliberate attempt to create a pacified Muslim but if we want to do something about this we need institutions, so we can have a collective. With mosques being depoliticized by the Charity Commission, how can we turn the mosques back into the centre of development and of the community organising?

Session 2: Working in the Academy: Can Transformative Knowledge be Produced in the Western University?

The second session, entitled, Working in the Academy: Can Transformative Knowledge be Produced in the Western University?, featured papers from Dr Amal Abu Bakare (lecturer at the University of Liverpool) and Sandew Hira (Decolonial International Network).

Sandew Hira focused on academia, and how academia works from a colonial perspective for higher education to produce universal knowledge as well as if Muslims can work with westernised establishments. On engagement, the generic question: “Should Muslims interact with the very establishment that may be responsible for their marginalization, discrimination, securitization and even incarceration?” cannot be answered in generic terms.

First you have to define what specific establishment you are talking about. The academic establishment is different from the political establishment, the media establishment or the military establishment. There is no generic establishment. There are specific establishments. Second you have to identify the specific actors from the decolonial communities who are going to engage with the specific establishment. In academia we are talking about the staff and the students. Third you have to define the specific actors in the establishment with whom you’re going to engage and what their power base is. Fourth you have to have a clear analysis of the dynamics of the interaction with the actors of the establishment and what you want to achieve with this interaction. Only then can engagement lead to meaningful results for the oppressed communities.

Amal Abu-Bakare wrote her paper on transformative knowledge of Islamophobia and if it can be produced in the university. She came to the conclusion of a cautious yes. In academia, transformative knowledge can be shared in university, however transformative action cannot. The university is not the best space for that to happen. Transformative knowledge is knowledge which creates awareness of social equality and empowers individuals to campaign for social change. When operating in the university, you compromise your ability to resist the powers you are part of.

Islamophobia is not different to other racisms, but why are other disenfranchised people not standing with us? Is this state induced? The identity has been created and discards the fact our faith is not the only binding factor but we are intersectional comprising different colours, ethnicities and ages as well as gender.

The idea of the Muslim world is is inseparable from the claim that muslims constitute a race rendering Muslims as racially distinct and inferior aimed to deny their demands for rights within european empires. Muslim intellectuals could not reject the assumptions of an inductable difference but responded that they were equal to christains deserving equal rights and fair treatment.

Islamophobia is not about contesting the faith, but rather to categorise a racial other in order to control the reality of the racial other, you control the content to which they can be measured as a person. All groups which suffer from racialisation face this.

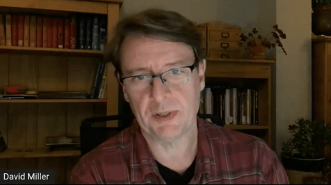

The panellists, Professor David Miller, Dr Sadek Hamid (independent academic), and Kasia Narkowicz (lecturer at Middlesex University London) shared their views on the papers.

Professor David Miller discussed his experience at the University of Bristol where he was dismissed for making comments against Zionism. His comments were cleared by multiple reports and investigations as not being anti-Semitic but despite this, he had to leave. Part of infringement on academic freedom by the Zionism movement is to silence voices. Zionists were part of the witch hunt that brought down Corbyn and sought to colonise academia to shut down criticism of Zionism and any support for Palestinians.

There are cases of anti-Semitism accusations being made against academics at multiple universities across the UK. This is a campaign funded and backed by the State of Israel where pro-Israel groups have significant lobbying power in Western countries. Israeli involvement in British institutions is not a recent phenomenon but has stretched right back to the existence of Israel from its founding.

Dr Sadek Hamid discussed the idea that universities that are truly free for the exploration of knowledge are becoming rare, clearly seen through the very hollow changes made by universities last year after the Black Lives Matter movement. The government’s criminalisation and closure of dissent is alarming, and it includes the surveillance of Muslim voices under the ‘Prevent’ policy. This is part of a weaponisation of antisemitism. Hamid has also been accused of antisemitism himself after making comments against Israel, and was treated very negatively by the Sunday times and the Home Office.

He is less hopeful for people of colour to be represented, as well as right wing narratives which have become widespread. In conclusion, he is hopeful in response to the question while also being realistic about the situation facing academia, especially for upcoming academics.

Kasia Narkowicz said the west and its institutions are built on the exploitation of bodies. Violence towards racialised beings isn’t at the sidelines of society but rather at the core. The western colonial wants to be seen as representative but without the disruption. Some institutions do cater to disadvantaged students and with their bodies, disrupt the very idea of who higher education is for.

Many communities find research undesirable because the research is done on them but not with them. There is recognition for the academic at the expense of for example, the Muslim target. Muslims are often forced to pledge allegiance to Britishness – often in a violent way. This is used by the British to keep the oppressed silent.

Narkowicz described that to engage with the establishment, it means to create more space which can open up doors to others without antagonising the establishment, and to attack the establishment by challenging the authority of the establishment and where the information comes from. Both strategies can work together but the first cannot make change without the second. There is also an unwillingness to do the bare minimum, such as changing the reading lists. Therefore, when as Muslims we are asked to take part in these studies, we need to be aware of refusal as an option. Anti-racism needs to be understood together with Islamophobia and they are not their own separate issues. Narkowicz explained that sometimes it feels important to leave the academic institution all together to draw knowledge from local communities so that we can be in constant conversation with them. This will force academics to be accountable and be in conversation with the people whose stories academics rely on for the production of knowledge.

Sunday, 12 December

Session 3: War and Law: Challenging the Violent State from Policing, Apartheid and Segregation to the Forever Wars

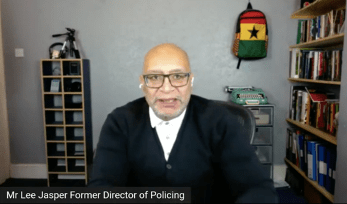

The third session, War and Law: Challenging the Violent State from Policing, Apartheid and Segregation to the Forever Wars, discussed papers from Lee Jasper (social justice campaigner) and Arzu Merali (researcher and one of the founders of IHRC).

Lee Jasper pointed to the deep anxiety and tensions that most ethnic minorities feel trying to find themselves within this society and suggests there is a conflict of experience racism whilst wanting to be patriots, which has been discussed by others such as Edward Said and Franz Fanon. Jasper expanded that it is vital for Diasporas to engage because of the symbiotic nature of the world today. The systemic inequalities are being exposed through the pandemic and from climate change, for example his own family in Caribbean have had to change their roof 7 times due to climate change.

Arzu Merali asked the question, what have we gained from working with the establishment? Citing previous events and conferences, such as the 2001 Durban conference UN vs Racism, Merali said it’s not that the world was very different since 9/11. Various groups worked together, mobilising around the issue of Palestine at that conference, despite the threats of violence against us from Zionist groups at the conference. We have veered towards UK and US issues, but we need to expand across borders more. Whatever we were going through we thought things would get better, and part of that was thinking that people were getting places in the establishment, despite some people like Lee there was also a lot of corruption, integrating “leaders” of the anti-racism movement into political parties. Those who do good within the system are often demonised and attacked in the press and become depressed. I’m seeing changes in the world, but the same things are happening, we are making the same mistakes again.

We were one of the first organisations to flag the new Blair anti-terrorism laws, mostly targeting particularly the Algerian community. The Algerian community was being used as a test subject for the wider Muslim community. We would protest and write to MPs, have legal campaigns, and we went through the same situation in 2000 with the new anti-terrorism laws. More Muslim organisations started taking note as well, as thousands of arrests took place on Muslims after 9/11. What we saw from these protests was to try to show that we could be the perfect citizen and therefore we will be accepted. But this was slightly naive and failed. We gave out cards to ‘Know Your Rights’ of how to react if you are stopped, the governments responded by doing their own know your rights cards. Both strategies (working with or not against) seem to have failed, and if these things were happening in the global south they would be highlighted in the news, but here they are just normalised. We need to be unrealistic and start thinking in unrealistic ways because the amount we can do realistically is being pushed back.

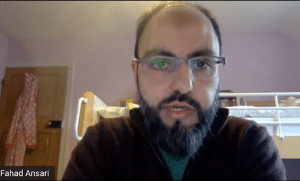

Panellists for session 3 included Reederwan Craayenstein (activist), Dr Rob Faure Walker (UCL Institute of Education), and Fahad Ansari (solicitor, Riverway Law).

Reederwan Craayenstein commented that if the IHRC did not exist, it would need to be created as it takes up causes that others are scared to tread. For some communities, they are important to make them feel like their troubles matter. Samuel Becket says to try, fail again and then fail again better. Socrates says the unexamined life is not worth living.

When Muslims in the UK talk around peace and democracy, it legitimises the UK’s role on the global stage. Peace to the UK is a strategic threat, especially amongst Muslims, Africa and South East Asia. What is needed is a mass movement, that is prepared to be radical, but you have to be prepared to pay the ultimate price, otherwise, you might as well pack up and go. We need radical movements outside that are willing to work with people inside the system. As when there are good people in the system they are cut down.

Dr Rob Faure Walker referenced his recent book, The Emergence of Extremism, and how has this word become linked with Islamophobia. He said, often in spaces where I am working with the police I’m allowed to speak whilst Muslims are shot down, and it continues even when I point it out. The police’s denial of racism is part of the problem. During Anti-colonial struggles, the British started referring to anti-colonial leaders as extremists, but then it started to come home and used on people here. Calling someone an extremist, often says as much about the person saying it as with the person being spoken about. Counter-extremism policies are then being deported all around the World, where the British gave training to the Xinjian authorities on counter-extremism. Wars are becoming more privatised wars. War on terror is a neoliberal way of taking money from the poor and putting it into the rich companies, often politicians have shares in these companies.

Julian Assange’s deportation is to enable future war crimes and cover-ups. There are anti-state activists and different levels of activism in order to get any solution to the existential crises, which are arguably the most complex situations that we face. We need to be anti-utopian. Assange reveals a gross injustice but also makes clear that despite the massive weight of the political class, judicial and press systems it’s all there for everyone to see. This demonstrates that it is almost impossible to make it invisible.

Fahad Ansari discussed the current COVID-19 situation in the UK, 145,000 people have died and there has hardly been a protest. The scandals with Boris, there were letters and some meme sharing, but no one on the streets, anywhere else in the world they would be. The idea here is to push you to vote for the opposition party, but the opposition party is just as bad. When the Rushdie situation happened people protested, Iraq was the same, but now a new bill comes in and people seem to only now realise that the government can take away your citizenship, but they could before. You are treated as a 2nd class citizen and even that can be taken away from you, and we’ve been moulded to submit and accept this. Therefore, we have to be unrealistic and we need to create a new vision.

The system is evil, and I don’t use that word sparingly. With someone like Priti Patel in power who is so biased. We are at the moment the world governments, activists and parts of the left, are not ready to envision a world without an apartheid state, they cannot see outside the vision of a two-state solution for Palestine.

Session 4: Serving the Community: Social Services or Community Programs?

The final session, Serving the Community: Social Services or Community Programs?, included papers from Sariya Cheruvalil-Contractor and Professor Ramón Grosfoguel.

Sariya Cheruvalil-Contractor discussed how the research projects she was involved with around Islamophobia and discrimination informed the British government. In the context of university campuses, Cheruvalil-Contractor said the campuses are characterised by super-diversity. The narrative was very different to top-down information that had been presented by interfaith leaders. Prevent and Islamophobic scrutiny is what led to young people experiencing a different kind of discrimination.

The research showed that young people wanted to challenge the extensive security they faced, particularly when facing islamophobia and organisations like prevent. There is hope for the future to work with Western Establishments.

Ramón Grosfoguel discussed the westernised left being caught between state centred solutions and the anarchist left which are anti-state. In the last 20 years there have been interventions about whether there should be a solution found within the state or outside of it. There is a need to interrupt the politics of domination. The state has problems and the solution won’t come from them. Different type of state from the long run because otherwise, the USA with its imperialistic invasions will take over. There must not be delusions that these solutions will come from the USA.

What happens in situations where the possibility is not available to do so? Many movements within metropolitan centres or imperialist countries it is difficult to have a progressive movement from a soft-left way. The commune cannot occupy the state by winning elections, but the struggle should never be stopped on the outside. What should you do in these countries like France or the UK? In France, 4 out of 5 candidates were not right-wing but fascist, with one left-wing candidate. In the UK there is the corrupt left, as they became the photocopy of the arena (the current arena being the right). When Tony Blair came to power he didn’t do anything different because he forced right wing ideals onto working-class people, which is why they lost the elections henceforth.

The panel consisted of Zareen Taj (Muslim Women’s Association of Edinburgh) and Abed Choudhury (Head of IHRC Advocacy).

Zareen Taj discussed the stereotype associated with being part of the system whereby people end up losing part of their integrity. Taj explains, the answer is not yes, no or maybe but all three depending on who you are the type of work you are passionate about. Covid-19 taught her that setting up local social care initiatives was still needed even though we’re living in a westernised “modern” country – and this is what should make it clear to us that we are in fact being oppressed. The mutual aid era is finished and we seem to be going back rather than using these structures recently implemented to improve our communities.

In Scotland, Taj worked with SACC, Stop the War and Muslim Women’s Association so that Muslim voices can be heard accurately and in an authentic manner. The question becomes, do you work with the establishment? In order to remain autonomous and self-policing you have to be careful about where you get funding.

Abed Choudhury discussed community engagement in terms of people engaging and working with different wider society organisations, and drew a distinction between how community organisations engage with the state, i.e., social organisations (community outreach) or political organisations (IHRC, fighting for rights).

Environment of Hate: The New Normal for Muslims in the UK Paperback (by Saied R. Ameli and Arzu Merali, 2015), describes how the community has responded to external factors implemented by wider society. There is no such thing as “good” Muslim/ “bad” Muslim – and people need to remember they do not need to conform to this narrative (not everything is a political movement). The Trojan horse scandal is a prevalent example of this where the Muslim population at the school were not doing anything out of the norm however, because of the toxic discourse, they ended up being in the centre of a media storm brewing islamophobia. The toxic discourse cannot be escaped, and Muslims are at the centre of a tornado facing hatred from all sides.

We should be engaging but we have to remember that even when we are doing what we are supposed to be doing, we can still be attacked. Political organisations that face these types of attacks should be aware of three responses to these attacks: Attacked, ignored or when engaged there is a sense of apathy. When engagement is present there is a sense of apathy, which is different to those community organisations, in order to de-legitimise their authority. Muslim organisations will say that media outlets are Islamaphobic, yet these concerns are ignored. Representatives from the EU were met by IHRC representatives regarding hate crime and there was almost no responses or acknowledgments from where solutions are supposed to come. Apathy is a problem because the work you do goes to waste.

On the “good Muslim / “bad” Muslim narrative, Abed elaborated, the good Muslim is expected to be pro zionist or abide by what a British society wants from you and in this way they are able to guide and manipulate via social engineering who can speak and to what extent Muslims can have an opinion. If you hold opinions that go against the current orthodox, you are then the bad Muslim or the terrorist. If Muslim organisations give into these, their voices seize to become authentic. Whatever orthodoxy is fashionable instead of what authentic beliefs are. The good Muslim is not a good Muslim unless he is what the state wants him to be.

All sessions were followed by a Q&A with the chairs and the audience. Finally, the conference ended with a summary of each session from Seyfeddin Kara and Saeed Khan, and vote of thanks from Massoud Shadjareh.

Closing statements

Massoud Shadjareh gave his thanks to the participants, panellists, those working behind the scenes and the viewers for joining the rich conversations. He identified that the Islamophobia we are facing is systemic, institutionalised, and not based on misunderstanding. We are living in an environment which is hostile and it is serving a purpose. We are being turned to others to give confidence and remove our confidence in ourselves, and we need to tackle both of those issues, as well as come together to challenge the institutional powers.

A special thank you to our supporting organisations:

- 5Pillars

- AIM (AhlulBayt Islamic Mission)

- Campaign Against Sanctions and Military Intervention in Iran CASMII

- Committee for Justice & Liberties

- Football Against Apartheid

- Friends of Al Aqsa

- Initiative for Muslim Community Development (IMCD)

- Inminds Human Rights Group

- Jewish Network for Palestine (JNP)

- Muslim Public Affairs Committee UK (MPAC UK)

- Prevent Digest

- Scottish Palestine Solidarity Campaign