HAMILTON, Bermuda – After almost eight years of captivity, each step of Khelil Mamut’s freedom is a little overwhelming.

The ocean, which he could hear only on windy days when the waves crashed beyond Guantanamo’s razor wire rimmed fence, is now something he can wade into.

People call him by his name, not 278, his internee serial number.

Then there was the horse he saw while walking one of the island trails on Thursday, the day he and three other Chinese citizens of the Muslim Uighur minority arrived in Bermuda. The animal made him stop suddenly, just to stare.

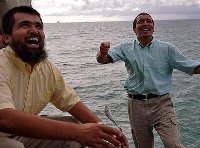

“How can I express it,” he said yesterday, describing the new tropical home where he now lives with the three other former Guantanamo detainees. “It is so great, so beautiful.”

“This may be a small island,” added Abdullah Abdulqadir. “But it has a big heart.”

The men spent yesterday with the Toronto Star, as they adjusted to life on the outside and reflected on a week that one local paper headlined: “From prison to paradise.”

Despite the backlash to their move, which has all Bermudians talking, they seemed insulated in their oceanside pink cottage, enjoying a fish lunch, a sunset swim and fielding the occasional media call.

They broke their composure only when a local imam visited them, embracing each fiercely.

The U.S. government is footing the bill for their food and accommodation until they can find work, which likely won’t be a problem since local companies have reportedly already made six offers.

Inside their three-bedroom apartment, where the carpet, curtain and walls match the pastel exterior, the men have managed to form a makeshift family.

American translator Rushan Abbas, who alternated yesterday between typing emails to their U.S. lawyers and kneading dough for a traditional Uighur dinner, joked that despite only being a few years older she considered the men her children.

Abbas worked for U.S. interrogators translating with Uighur detainees when she first started at Guantanamo in 2002.

Then she “switched sides,” she said, and started working for defence attorneys. She came here for a few days to make the transition smoother since Abdulqadir and Mamut know only limited English, and the other two men, Salahidin Abdulahat and Ablikim Turahun, don’t understand at all.

The men also have the assistance of a retired Bermudian army major, Glenn Brangman, who now works with the government. With his booming voice and hibiscus-patterned surf shorts, Brangman has become their energetic guide.

Two weeks ago the scene for these men in Camp Iguana – the U.S. military’s name for the prison where they were detained in Guantanamo – couldn’t have been more different. On June 1, Abdulqadir approached a small group of journalists during a rare unscripted moment in a prison where the message is tightly controlled.

“Who’s in charge?” Abdulqadir asked, as reporters, including one from the Star, stood mute on the other side of the fence due to rules that forbid communication between journalists and prisoners.

Abdulqadir and another detainee then quickly displayed a sketch pad where they’d written their message in crayon, managing to pull off the detention centre’s first public protest.

“We need to freedom (sic),” said one page.

Ten days later, a secret pre-dawn private flight whisked them away from Guantanamo to this tourist mecca.

There’s no doubt the four men stand out in this self-governing British territory that’s only 54 square kilometres – less than half the size of Guantanamo’s U.S. naval base.

There’s no Uighur population here and when locals are asked if there’s an Asian community, most point to a Japanese resident who opened a restaurant.

Their arrival has consumed the local media and parliament. Opposition members tabled a no-confidence motion on Friday to oust Bermuda’s Premier Ewart Brown, arguing that his covert deal with U.S. President Barack Obama was indicative of his “autocratic” leadership.

“We don’t know who these men are,” opposition minister Shawn Crockwell said in an interview with the Star.

“All of a sudden there’s an association between Bermuda and terrorism. Whether or not these men are or not, there’s that association.”

The men yesterday said they hoped they could shake the terrorist label.

“There’s absolutely no hard feelings toward the U.S.,” said Abdulqadir.

“There are some people accusing us, labelling us as dangerous people, but that’s not true at all.”

For years, the debate over the Uighur detainees, who range in age from 30 to 38, was whether they were Guantanamo victims or men who had formed links with Al Qaeda to support their opposition to China’s rule.

The men said they fled China in the summer of 2001 for neighbouring Afghanistan – the two countries share a tiny stretch of border – because they could not get passports enabling them to go elsewhere.

After the 9/11 attacks and the U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001, the men were caught by Pakistani services and sold to the United States for a bounty.

The Pentagon accused them of training at “Al Qaeda-linked” camps and belonging to the East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM), which opposes China’s oppression of Uighurs.

In September 2002, after the men had been in custody for almost a year, the ETIM was designated a terrorist organization by the U.S. State Department.

The listing itself was criticized by some who accused the United States of succumbing to China’s pressure at a time when Beijing’s support was sought for the upcoming war in Iraq.

During years of litigation, the D.C. courts slammed the inadequacy of the government’s evidence, eventually pushing the Bush administration to concede that the Uighurs were no longer designated “enemy combatants.”

This administrative reclassification, which cleared the men for release, prompted one District Court judge to quip: “The government’s use of the Kafkaesque term `no longer enemy combatants’ deliberately begs the question of whether these petitioners ever were enemy combatants.”

Yesterday, the men said the toughest time in their captivity was when Chinese interrogators were allowed on the base in 2002.

They also talked of their year inside Camp 6, where they were kept in solitary confinement and only meals and calls of other prisoners broke the monotony of the day.

After a D.C. judge ordered them released last October, they were transferred to Camp Iguana, a separate prison of enclosed wooden huts, perched high on a rocky cliff overlooking the ocean.

But when the United States denied them refuge and no other country would accept them, they were trapped in a legal limbo until last week.

Another 13 Uighur detainees, heading for the tiny Pacific island of Palau, still remain in Guantanamo, as

does Canadian Omar Khadr.

Some residents here were angry that Bermuda accepted men other Western nations refused to take, while others say the men will integrate well.

“I feel people need somewhere to go. These guys haven’t done anything wrong and have been locked up,” said Carol Turini, a 70-year-old cab driver who retired from a job in the immigration department eight years ago.

“Why not?”

Their American lawyer, Sabin Willet, said one of the most poignant moments for him came when they were shopping for new clothes as a local talk radio show was airing irate callers saying Bermuda was harbouring terrorists.

Hearing the radio, and then recognizing the men, the storeowner looked at them and said, “Well, I welcome you here.”