Khaled Gareb, a Muslim American living in San Francisco, did not need to read a sociological study to learn that his community has suffered from increasing hostility since 11 September 2001.

“Neighbors became suspicious, people shout epithets at the entryway to our mosque,” he said, sitting on the crimson carpet of the Masjid Darussalam mosque.

Masjid Darussalam is a pocket of tranquility suspended over the cramped, grimy streets of San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. Almost entirely unmarked on the street, one climbs three flights of stairs before entering its graceful and open space that embodies the particular nature of all mosques, and which has been carved out of the third floor of an office building. Below it is a community housing organization.

Now in charge of public relations at Masjid Darussalam, Gareb moved to California 16 years ago from Yemen. After spending two years in Sacramento, he settled in San Francisco and has since watched the mosque’s community grow and diversify over the years.

When I spoke to him after Friday prayers on a warm afternoon in late spring, the mosque was emptying of its worshipers who had come to San Francisco from all over the world — Nigeria, Yemen, Malaysia and Palestine. Many of them were going back to their jobs, some of them in the city’s nearby financial district.

Suspect class

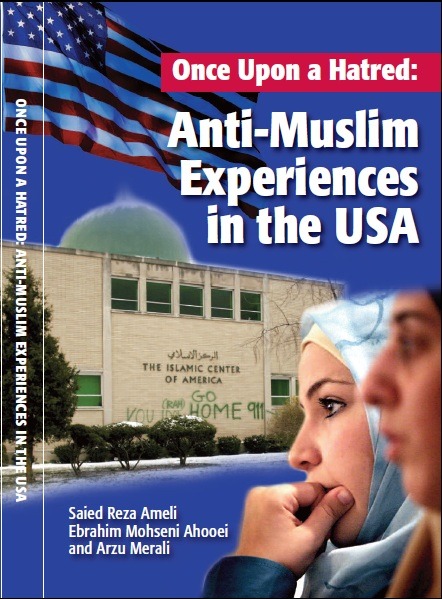

As early as 1993, scholars asserted that the US is “home to the most heterogeneous Muslim community at any time or place in the history of the world” (“Once upon a hatred: Anti-Muslim experiences in the USA,” Islamic Human Rights Commission, 4 May).

Muslim Americans come from more than 80 different countries and four continents; they occupy different socioeconomic classes, subscribe to a variety of sects and pursue all manner of jobs.

Yet this highly diverse population has been shrunken into a single suspect class, unified now by its experience with Islamophobia. A widely debated term, “Islamophobia” has nevertheless “gained currency as the symbolic representation of the phenomenon of otherizing Muslims,” Dr. Hatem Bazian of the University of California at Berkeley told The Electronic Intifada. Bazian teaches law, philosophy and Islamic Studies and is active in the local Palestinian solidarity movement.

Two studies that attempt to quantify the pervasiveness and examine the many expressions of Islamophobia in the United States were published last month. Both studies survey a sample population of Muslim Americans, gaining insight into respondents’ experience with discrimination, hate-crimes and harassment.

The first, produced by the UK-based Islamic Human Rights Commission, surveys Muslims residing in California. The second, funded by the One Nation Foundation, looks specifically at the San Francisco Bay Area, a region that is comprised of six counties and includes the cities of San Francisco, San Jose, Oakland and Berkeley as well as the many smaller towns and suburbs. The two studies were conducted separately, and the results of each affirm and complement the other.

Just a sample of the findings provides significant insight into the magnitude of the issue.

Physical attacks

The Islamic Human Rights Commission reveals that 29.9 percent of all respondents in the state of California had experienced a hate-motivated physical attack, the highest figure found so far.

Not far behind, however, in the designated seat of liberal America, the San Francisco Bay Area of California, 23 percent of respondents reported being victims of a hate crime.

Similarly, the Islamic Human Rights Commission found that, in California, 37.9 percent of respondents had been “overlooked, ignored or denied service in a public” due to prejudice, while in the Bay Area, 40 percent of respondents said they had experienced some sort of discrimination.

“These numbers alone don’t say anything that is surprising, but they confirm what people already knew about their community,” Zahra Billoo told The Electronic Intifada. Billoo is the Executive Director of the San Francisco Bay Area chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR).

“These studies are very helpful to advocates, because overall we lack data about the Arab and Muslim communities. This is what other marginalized communities have started doing: making their own census reports to try to quantify their communities and communities’ experiences,” Billoo said.

Released last May, the Islamic Human Rights Commission’s nearly 200-page publication, addresses the many forms in which Islamophobia currently manifests and historically manifested itself in America.

The publication also identifies the theoretical, historical and institutional obstacles to studying anti-Muslim behavior; chronicles the over 100-year history of Muslims in North America; briefly notes the interaction between Native Americans and Muslims that pre-dates the arrival of Columbus; and finally, conducts a survey of Muslim experiences with hate crimes in California.

The study emphasizes that rather than merely collating data on the instances of hate expressed on the individual level, “The project seeks to examine and present the systemic nature and root of societal prejudice.”

The “Bay Area Muslim study: Establishing identity and community” report was also published in May. Authored by Bazian and Dr. Farid Senzai, this report was commissioned by the One Nation Bay Area Project, a philanthropic foundation.

Senzai’s and Bazian’s publication provides demographic information and data on the Muslim population in the Bay Area. In addition to establishing a skeletal portrait of the Bay Area’s Muslim population, the study seeks to demonstrate the extent to which the community has been “otherized.”

“Demonized”

The publication also recommends a number of steps for tackling this state of alienation, including building coalitions with the non-Muslim community and, for policymakers, challenging the anti-Muslim narrative.

Bazian pointed to a structural impetus that perpetuates the “otherization” of Muslims in the post-11 September 2001 political landscape:

“Everyone is still busy with symbolic, political aspects of Islamophobia — like the head scarf or the minarets in Switzerland — because essentially they don’t want you to begin to critique the underlying shifting of resources away from human needs to fear, death and destruction and aggressive policies, all of which are rationalized by the presence of this demonized other.”

For Bazian, the recent publications represent an important advance in the discussion of Islamophobia. “There are a number of studies which are coalescing to create an intellectual foundation on which more systematic studies can emerge to provide a substantial amount of literature on Islamophobia,” he remarked.

Bazian is also a co-founder of Zaytuna College, which aims to be the first accredited Muslim College in the US, and is the founder of The Journal for Islamophobia Studies. Bazian believes that the academy, with all of its colonialist faults, can serve as “an important site for exploration and a place where ideas are shaped.”

However, at present the academy persistently mirrors the social hostility and bigotry to — and fear of association with — Muslims. “Islamophobia is highly understudied in academic circles and specialized research centers,” he said. “A lot of institutions, even so-called progressive ones, are distancing themselves from the study of Islamophobia, because they don’t want to appear close to the category of Islam.”

“Scared” of FBI

Among the reasons why greater attention to Islamophobia is required is the lack of reliable data on the problem from the authorities.

While the FBI has collected “hate-crime” statistics since 1992, their accuracy is dubious. The Islamic Human Rights Commission’s report explains its study was motivated, in part, by the “failure and unreliability of statistics collecting on the basis of reporting.”

Indeed, the FBI reports a relatively low number of “hate-crimes” against Muslim Americans compared to other minority and vulnerable groups, a statistic that has been cited by some as proof that Islamophobia is a “myth” (“Hate crime stats deflate Islamophobia myth,” National Review Online, 11 January).

“Lack of evidence does not mean the lack of existence of Islamophobia,” Bazian argued. “The FBI data doesn’t capture, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.”

That the FBI has proliferated informants and enacted entrapment operations in Muslim communities throughout the country is, perhaps, one reason Muslims are increasingly reluctant to engage law enforcement agencies for help.

The Council on American-Islamic Relations’ Zahra Billoo likens the apprehension a Muslim American feels toward reporting incidents to the FBI to that of an undocumented person calling for help from the local police department that is known to collaborate with the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency.

“The FBI has targeted the Muslim community so people are scared of calling them,” Billoo said.

Indeed, the authors of both surveys emphasize the difficulty in collecting accurate data on the Muslim American population, for the very revealing reason that respondents are frequently wary to answer certain questions. Nevertheless, the studies provide compelling evidence that Muslim Americans continue to be an at-risk group whose vulnerability US civil and state institutions must address.

“It is a long-term struggle to reshape the production of knowledge about Muslims so that it takes into account the multiplicity of the community,” said Bazian. “It is important that the study of Islamophobia points to the systemic production of Islamophobia.”

Charlotte Silver is a journalist based in occupied Palestine and San Francisco. Follow her on Twitter: @CharESilver. The article above was first published on 25 June 2013 at electronic intifada.