According to the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, estimates indicate that the total number of civilians and prisoners of war murdered in Nanjing during the first six weeks of the Japanese occupation was over 200,000. These estimates are borne out by the figures of burial societies and other organisations which testify to over 155,000 buried bodies. These figures do not take into account those who died due to burning, drowning, and other means (i).

According to the verdict of the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal on 10 March 1947, there were “more than 190,000 mass slaughtered civilians and Chinese soldiers killed by machine gun by the Japanese army, whose corpses have been burned to destroy proof. Besides, we count more than 150,000 victims of barbarian acts buried by the charity organisations. We thus have a total of more than 300,000 victims.”(ii) The International Military Tribunal for the Far East also estimated that between 20,000–80,000 women were raped at the hands of the Japanese soldiers during the Massacre of Nanjing.

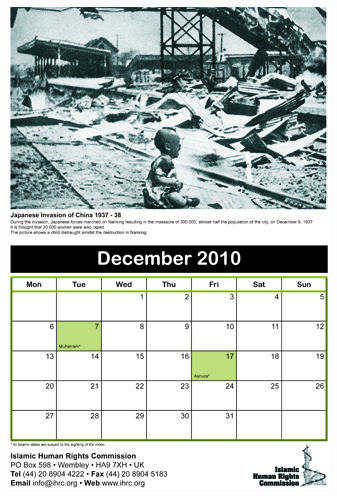

Invasion of Nanjing

After successfully invading Shanghai by mid-November 1937, the Japanese Army moved to capture Nanjing which was then the capital of the Republic of China. The city was destined to fall as the Chinese High Command, wishing to preserve its best soldiers for future battles, withdrew the majority of its troops, leaving behind an army of young and inexperienced conscripts. By 7 December 1937 both the Chinese government and the President of the Republic had left the capital, leaving the fate of its population to an International Committee led by John Rabe, a German businessman who was a resident of Nanjing and a member of the German Nazi party.

Upon entering the city, the Japanese army unleashed a tirade of brutal and indescribable inhumane suffering on the population. Eyewitness accounts from both the native population of Nanjing and Western residents describe the disturbing war crimes perpetrated by the Japanese troops on both the civilians of Nanjing and the prisoners of war. These accounts describe how over a six week period, Japanese troops unleashed a tirade of rape, murder, theft and arson against an unarmed population.

The March to Nanjing

Although the Nanjing Massacre is generally described as having occurred over a six-week period after the fall of Nanjing, the war crimes committed by the Japanese army were not limited to that period. A number of atrocities were committed by the Imperial army as it advanced from Shanghai to Nanjing. According to one Japanese journalist embedded with Imperial forces at the time, the fast past in which the Japanese army was advancing was due to the “tacit consent among the officers and men that they could loot and rape as they wish.”(iii)

In his novel Living Soldiers (Ikiteiru Heitai), based on interviews conducted with troops in Nanjing during January 1938, novelist Ishikawa Tatsuzo described in detail the atrocities committed by the 16th Division of the Shanghai Expeditionary Force on the march to Nanjing.(iv) Towns such as Songjian and Suzhou witnessed horrific massacres and mass rapes. Eye witness accounts describe the use of indiscriminate shooting, rape, mutilation and arson.

Execution of Chinese POWs

Immediately after the fall of Nanjing, Japanese troops embarked on a search and kill policy which led to the killing of tens of thousands of defeated soldiers. What was probably the single largest massacre of Chinese troops occurred along the banks of the Yangtze River on December 18 in what is called the Straw String Gorge Massacre. Japanese soldiers tied the POW’s hands together before dividing them into 4 columns and opening fire at them. In another incident at Taiping Gate, Japanese troops gathered 1,300 Chinese soldiers and civilians and killed them. The victims were blown up with land-mines, then doused with petrol before being set on fire.(v) It is estimated that at least 57,500 Chinese POWs were killed.

American news correspondents, F. Tillman Durban and Archibald Steele reported that they had seen bodies of killed Chinese soldiers forming mounds six feet high at the Nanking Yijiang gate in the north of the city.(vi) It is alleged that Prince Asaka, a member of the Imperial royal family and the General in charge of the Japanese forces in Nanjing issued an order to “kill all captives,” captured in the takeover of the city.(vii) While some sources record that Prince Asaka personally signed the order for Japanese soldiers to “kill all captives”,(viii) others claim that lieutenant Colonel Siam Cho, the Prince’s aide-de-camp, sent this order without the Prince’s knowledge or assent.(ix)

While the extent of Prince Asaka’s responsibility for the massacre remains a matter of debate, the ultimate responsibility for the massacre and the crimes committed during the invasion of Nanjing must lay with the Emperor Hirohito, who on August 5th 1937 issued a directive removing the constraints of international law on the treatment of Chinese prisoners.(x) This directive also advised staff officers to stop using the term “prisoners of war”.(xi)

Rape

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East estimated that at least 20,000 women had been raped in Nanjing by Japanese soldiers. Victims of the rape included infants, the elderly and pregnant women.(xii) Those giving testimonies at the tribunal described how soldiers systematically searched door-to-door for young girls, taking them captive and gang-raping them. Eye witness accounts, soldier testimonies and photo evidence portray how these women were often killed immediately after the rape, often through explicit mutilation(xiii) or by the stabbing of a bayonet, a long bamboo stick,(xiv) or other objects such as bottles into the victim’s vagina.

On 19th December 1937, Reverend James M. McCallum wrote in his diary, “Never have I read or heard of such brutality. Rape! Rape! Rape! We estimate at least 1,000 cases a night, and many by day.”(xv) On March 7, 1938, Robert O. Wilson, a surgeon at the American-administered University Hospital in the Safety Zone, wrote in letters to his family dated 15th and 18th December 1937, “The slaughter of civilians is appalling. I could go on for pages telling of cases of rape and brutality almost beyond belief. Last night the house of one of the Chinese staff members of the university was broken into and two of the women, his relatives, were raped. Two girls, about 16, were raped to death in one of the refugee camps. In the University Middle School where there are 8,000 people the Japs[sic] came in ten times last night, over the wall, stole food, clothing, and raped until they were satisfied.”(xvi)

In his diary kept during the Massacre, the leader of the Safety Zone, John Rabe, wrote endlessly about Japanese atrocities. On 17th December, he wrote “Last night up to 1,000 women and girls are said to have been raped, about 100 girls at Ginling College Girls alone. You hear nothing but rape… What you hear and see on all sides is the brutality and bestiality of the Japanese soldiers.”(xvii)

Pregnant women too were not spared the inhumane treatment. There were countless cases of pregnant women being bayoneted in the stomach after being raped. A survivor of one of these attacks, Tang Junshan, described how “The seventh and last person in the first row was a pregnant woman. The soldier thought he might as well rape her before killing her, so he pulled her out of the group to a spot about ten meters away. As he was trying to rape her, the woman resisted fiercely … The soldier abruptly stabbed her in the belly with a bayonet. She gave a final scream as her intestines spilled out. Then the soldier stabbed the foetus, with its umbilical cord clearly visible, and tossed it aside.”(xviii)

The International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone

As the Japanese army approached Nanjing, the vast majority of westerners who lived in the city fled. Fifteen of those remaining formed a committee called the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone.(xix) German businessman John Rabe was elected as its leader because of his status as a member of the Nazi Party and due to the existence of the German-Japanese bilateral Anti-Comintern Pact. The safety Zone was established in the western quarter of the city.

Nevertheless, even in the Nanjing Safety Zone where the Japanese troops were supposed to respect their bilateral pact with Germany, Rabe wrote that from time to time the Japanese troops would enter the Safety Zone at will, carrying off a few hundred men and women, who were then summarily executed, often after being raped.(xx) By February 5, 1938, the International Committee had forwarded to the Japanese embassy a total of 450 cases of murder, rape, and general disorder by Japanese soldiers.(xxi)

The End of the Massacre

It was not until the establishment of the “weixin zhengfu” (the collaborating government) in 1938 that order was gradually restored in Nanjing and the atrocities began to decline.

War Crimes Tribunal

Shortly after the surrender of Japan in the Second World War, the primary officers in charge of the Japanese troops at Nanking were put on trial. General Matsui was indicted before the International Military Tribunal for the Far East for “deliberately and recklessly” ignoring his legal duty “to take adequate steps to secure the observance and prevent breaches” of the Hague Convention. Hisao Tani, the lieutenant general of the 6th Division of the Japanese army in Nanking, was tried by the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal.

Other Japanese military leaders in charge at the time of the Nanking Massacre were not tried. Prince Kan’in, chief of staff of the Japanese Army during the massacre, had died before the end of the war in May 1945. Prince Asaka was granted immunity because of his status as a member of the imperial family.(xxii) Siam Cho, the aide of Prince Asaka, who some historians believe issued the “kill all captives” memo, had committed suicide during the defence of Okinawa.(xxiii)

Verdict

In the end the Tribunal connected only two defendants to the Rape of Nanking. Matsui was convicted of count 55, which charged him with being one of the senior officers who “deliberately and recklessly disregarded their legal duty [by virtue of their respective offices] to take adequate steps to secure the observance [of the Laws and Customs of War] and prevent breaches thereof, and thereby violated the laws of war.”

Hirota Koki, who had been the Foreign Minister when Japan conquered Nanking, was convicted of participating in “the formulation or execution of a common plan or conspiracy” (count 1), waging “a war of aggression and a war in violation of international laws, treaties, agreements and assurances against the Republic of China” (count 27) and count 55. On November 12, 1948, on the basis of a simple majority of the eleven judges, Matsui and Hirota, with five other convicted ‘Class-A’ war criminals were sentenced to death by hanging. Eighteen others received lesser sentences. General Hisao Tani was also sentenced to death by the Nanking War Crimes Tribunal.(xxiv)

Although Japan has acknowledged the occurrence of wartime atrocities by its Imperial Army, disputes over the historical portrayal of these events continue to cause tensions between the two countries. Although on August 15, 1995, the Japanese prime minister Tomiichi Murayama apologised for Japan’s wrongful aggression and the great suffering that it inflicted in Asia, many in China have criticised Murayama for not providing a written apology for the Rape of Nanjing.

END NOTES:

- Judgment International Military Tribunal for the Far East, Chapter 8, Paragraph 2, p. 1015

- Tokushi Kasahara, Le massacre de Nankin et les mécanismes de sa négation par la classe politique dirigeante, http://www.ihtp.cnrs.fr/IMG/pdf_interventionsnankin-francais.pdf

- Cummins, Joseph The World’s Bloodiest History (2009), p. 149

- Katsuichi Honda, Frank Gibney, The Nanjing massacre: a Japanese journalist confronts Japan’s national shame, pp. 39–41

- Bristow, Michael (2007-12-13). “Nanjing remembers massacre victims” BBC News

- Hua-ling Hu, American Goddess at the Rape of Nanking: The Courage of Minnie Vautrin, (2000) p.77

- Bergamini, David. Japan’s Imperial Conspiracy (1971) p. 23.

- i David Bergamini, Japan’s imperial Conspiracy, (1971) p. 24

- Iris Chang, The Rape of Nanking (1997) p. 40

- Akira Fujiwara, Nitchû Sensô ni Okeru Horyo Gyakusatsu, Kikan Sensô Sekinin Kenkyû 9, 1995, p. 22

- Fujiwara, Akira (1995). “Nitchû Sensô ni Okeru Horyotoshido Gyakusatsu”. Kikan Sensô Sekinin Kenkyû 9: 22 Paragraph 2, p. 1012, Judgment International Military Tribunal for the Far East.

- “A Debt of Blood: An Eyewitness Account of the Barbarous Acts of the Japanese Invaders in Nanjing,” 7 February 1938, Dagong Daily, Wuhan edition

- Military Commission of the Kuomintang, Political Department: “A True Record of the Atrocities Committed by the Invading Japanese Army,” compiled July 1938

- Hua-ling Hu, American Goddess at the Rape of Nanking: The Courage of Minnie Vautrin, 2000, p.97i M. E. Sharpe Zhang, Kaiyuan. Eyewitness to Massacre: American Missionaries Bear Witness to Japanese Atrocities in Nanjing (2001)

- Woods, John E The Good man of Nanking, the Diaries of John Rabe (1998) p. 77.

- Celia, Yang The Memorial Hall for the Victims of the Nanjing Massacre: Rhetoric in the Face of Tragedy (2006)

- Askew, David The International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone: An Introduction

- Woods, John E The Good man of Nanking, the Diaries of John Rabe (1998) p. 274.

- Woods, John E The Good man of Nanking, the Diaries of John Rabe (1998) pp. 275–278..

- Herbert Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan (2000) p.583, John Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (1999) p.326

- Thomas M. Huber, Japan’s Battle of Okinawa, April–June 1945, Leavenworth Papers Number 18, Combat Studies Institute, 1990, p.47

- Bix, Herbert “Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan” (2001) Perennial: 734.

{jathumbnail off}