Hindsight and the scourge of Islamophobia

Volume 2 – Issue 1 – February 2020 / Jumadi II 1441

Editorial

It is a sign of how far we have regressed that Muslim civil society veterans in the UK fondly remember the Satanic Verses Affair as the high point of community unity and activism. In the late 1980’s it took the besmirching of the beloved Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) to bring together the diverse strands of the community and give birth to what represented nothing short of a political awakening. In the years that followed the experience of campaigning during these events spawned an array of representative organisations raising hopes that a newfound political consciousness would translate into effective political power. However, barring the odd notable exception such as the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the history of Muslim politics has been dominated by powerlessness, fractiousness, sycophancy and strategic miscalculations.

Charting the trajectory of UK Muslim activism, our lead article by IHRC’s head of research Arzu Merali, explains its decline by reference to a wider Zionist, neocon, strategy of divide and rule, led by think tanks such as the Rand Institute. Using the old carrot and stick approach, western governments have co-opted and/or coerced independent Muslim voices into such lassitude that many of us are able to raise even a whimper of protest, let alone organised campaigns, against policies and actions that progressively undermine our religious and social life. Where we are outraged enough to speak out, such as for example on the issue of Islamophobic anti-terrorism legislation, the response has often fallen into the frameworks constructed for us by our adversaries thereby advancing their agenda instead of securing our own strategic objectives.

While she laments the slide into a trap set by our adversaries, this is not a nostalgic plea for a return to some imagined halcyon days. Rather it is a genuine, heartfelt call on the community by someone who daily lives and breathes the Muslim experience to reflect and reset if we are to ever become the kind of force our numerical presence and collective talents justify.

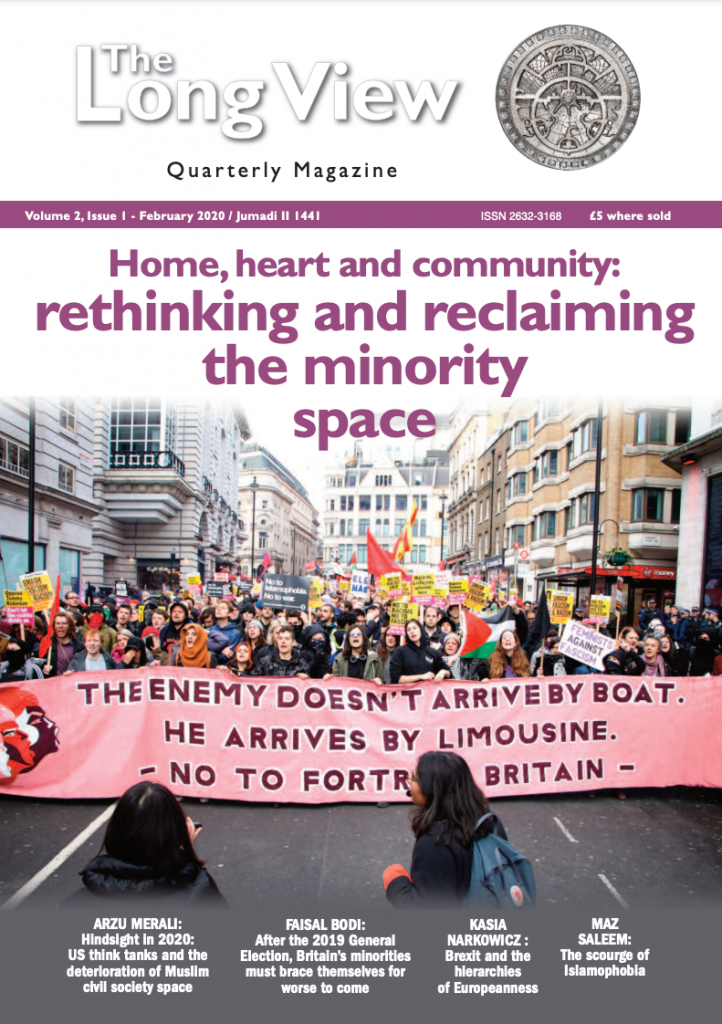

The recent election of a party led by an opportunistic xenophobe and misogynist will do little to ease things for Britain’s Muslims and racialised minorities in general, not least of all because the poll was driven overwhelmingly by an issue that has its roots in racism: Brexit. The first of our articles on the subject by Faisal Bodi identifies the underlying causes for the popular support for the party that recast itself as the party of Brexit, paying particular attention to the flocking of Labour’s traditional working class base to the dog-whistle of immigration. He highlights how Islamophobic and racist meta-narratives have been placed centre-stage creating an environment of hate which encourages the popular expression of hitherto latent sentiments. While some have called for Labour to adjust to the new reality, something that effectively amounts to a policy of appeasing racism, others have urged the party to reconnect in new ways with people whose economic disaffection is vocalised in the language of race. There is no quick fix to the “white tide” sweeping Britain, argues Bodi, and things may have to get a lot worse for those on the receiving end before they get better.

The second article on Brexit, by Kasia Narkowicz, looks at how the issue has brought into sharp relief the racism and discrimination faced by people of Eastern European origin. The arrival of these expatriates in large numbers after 2004 coincides with an increase in anti-immigrant sentiment/hysteria in Britain. While Muslims are often depicted through old racist tropes of potential terrorists and sexual predators, Eastern Europeans are seen to be responsible for stealing jobs and resources. Since they are also likely to feel the force of racist post-Brexit immigration policy, it is a travesty that their plight is usually overlooked. Narkowicz says that while many Europeans from the former Soviet bloc have made Britain their home, they feel far from at home. They are scared and insecure. Narrowing, increasingly racialised, definitions of Britishness and rising hostility make these white and Christian migrants feel more and more unwelcome.

Our final article comes from a campaigner who was reluctantly thrust into anti-racism activism after her father was murdered by a white supremacist as he walked home from evening prayers at his local mosque in 2013. The killer of 82-year-old Mohammed Saleem would later be found to be responsible for planting bombs at mosques in the same area of the West Midlands. Maz Saleem recounts the Islamophobia she faced from a criminal justice system that initially treated her family as the prime suspects and showed little sensitivity to religious sensibilities pertaining to burying the deceased. But her focus is much wider, explaining the term ‘institutional Islamophobia’, and documenting its presence across the gamut of society from security legislation to education and health care.

The submissions this issue paint stark pictures of societal crises and upheaval. Yet from these analyses comes the possibility of joined up thinking and conversation. From there, maybe even action. Let’s make a start.