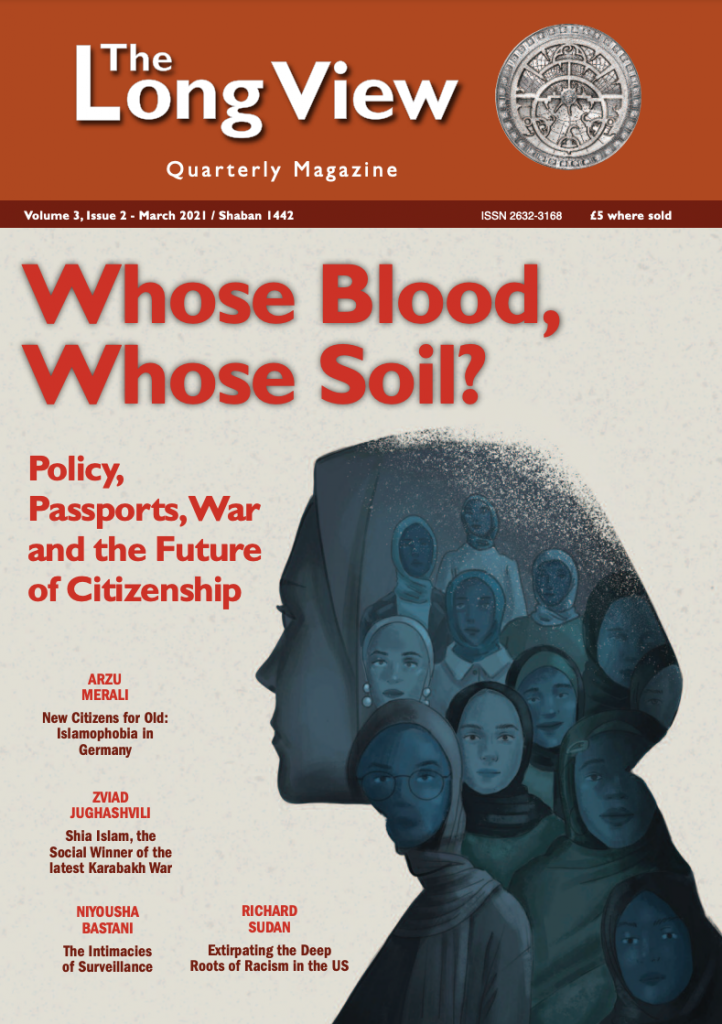

Whose Blood, Whose Soil? Policy, Passports, War and the Future of Citizenship

Volume 3 – Issue 2 – March 2021 / Shaban 1442

Editorial

Daily in the news there is some case or another that calls into question claims by Western(ised) or European(ised) states that they are beacons of equality. Played out on a grand scale, these cases focusing on nationality, religious dress, discriminatory policing and law, surveillance and even social disapprobation, all connect centrally with the idea of citizenship.

This term, in its formal legal sense, of course means the legal rights of nationality. These days, as political space narrows, it has also come to mean the rites of nationality – specifically what a person should do to attain nationality and what they should believe to be deserving of that nationality. This latter trend has become a dominant theme in the European context, led, so argues our first essay, by trends in Germany. Formerly, the emotional aspects of citizenship – the need to belong to and feel belonged by your country – were part of the narrative of what it means – as individuals and groups – to be part of a nation. This was evidenced in e.g. British notions of multiculturalism and the adoption / adaptation of the term in the German context. This scenario in Germany has not only drastically been reversed, according to Arzu Merali in ‘New Citizens for Old’, it has now become a dominating narrative of citizenship for minoritised communities, especially Muslims. Set to fail in their aspiration to be fully considered citizens, Muslims find themselves viewed in political and legal terms as unworthy – labelled homophobic, sexist, backward and resistant to ‘integration’. This is compounded by a growing resurgence in the idea that citizenship and belonging are based somehow on blood – or put more drastically racial purity – as the real determinants of who belongs where. All is not doom and gloom however, as Merali highlights the possibilities and contradictions in the German political and legal landscape that set good precedent and can provide the basis for a truly new and inclusive form of citizenship.

These ideas of who is ‘worthy’ and who has ‘rights’ can be found internalised in Muslims’ views of themselves and each other. Our second and third essays look at this from different vantage points. Discussing the recent (continuation of) war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Zvaid Jugashvili looks at the almost unreported role and influence of Shia Islam in the region. In this scenario, people have literally given blood to establish who ‘belongs’ on this soil. Highlighting the prevalence of Shia Muslims in Azerbaijan and its forces, Jugashvili uncovers the influence of Shia Muslim narratives in this battle over the Ngorno Karabakh region, compared to the previous conflagration in the 1990s. This influence, he argues, resets regional dynamics in surprising ways. Whilst popular international Muslim narratives during the recent battles either promoted or did not dispel the idea of this being a battle between Sunni, ethnic Turks, supported by their Sunni Turkish brethren (and to some extent Sunni fighters from elsewhere), the local realities were something entirely different. The events, when viewed through this lens, challenge Muslims in their own expectations of who is a Muslim and what Muslim commonalities are.

Niyousha Bastani’s piece takes us right back to the UK and the pervasive influence of the Prevent policy in the everyday lives of Muslims. In Intimate Surveillance, she argues that the normative lens of the Prevent policy, as averred to also in Merali’s piece, focussing on Muslims as sexually deviant, and particularly homophobic, has impacted on how Muslims think about themselves and each other – right down to the minutiae of everyday interactions between family members. This type of racist gaze, internalised, affects both establishment figures and those seeking to represent Muslims as their leaders, as well as critical thinkers. So unassuming and second place have these ideas become that the critical functions of representation and resistance are compromised. This dissonance then reinforces the ideas and feelings of exclusion, and stifles expectations on the part of those minoritised, for inclusion.

In our final essay, Richard Sudan looks at the role of white supremacy and policing as a foundational part of what the USA is today. How can there ever be equal citizenship when the very notion of who is human is contested from the outset of the establishment of the country? As Sudan points out, when black people and people of colour have been delimited in law as less than worthy, policing becomes an inevitable tool of white supremacy. To escape from this vicious cycle, the US must become something entirely other, shorn completely of all institutional (and foundational) notions of white supremacy. Without this, last summer’s marches and calls for equality and justice cannot become a reality.

This is an important intervention in unmasking the hidden problems that prevent the realisation of transformative citizenship. All our essays hit upon the need for reimagining or regaining the narratives of belonging and being. We hope this issue helps bring that necessity to a quicker fruition.