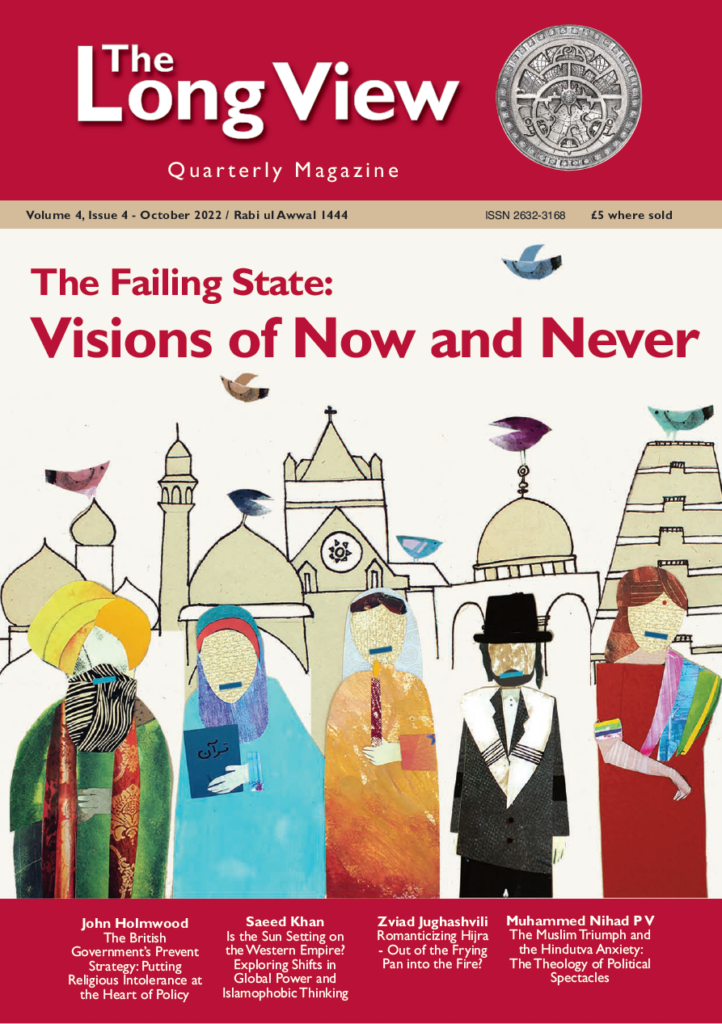

The Failing State: Visions of Now and Never

Volume 4 – Issue 4 – October 2022 / Rabi ul-Awwal 1444

Editorial

Recent years have seen a proliferation of so-called think tanks turn their attention to defining the position Muslims, as a community, should occupy in Britain. While most of the headlines are usually hogged by the unabashed Islam-bashers in the Henry Jackson Society, others carry on their nefarious work behind the scenes, rarely coming into public view. The Tony Blair Institute is one such actor, as is the subject of our first offering in this issue of the Long View, Policy Exchange. Policy Exchange is often described as the most influential of Britain’s right wing think tanks and criticised for being beholden to corporate interests, especially the tobacco industry. Although it is a registered charity, something that gives it a veneer of independence, information about its funding is very opaque and tightly guarded.

The job of think tanks is to provide policymakers with academic/intellectual legitimacy for their ideas. This is not to say that policies spring up from rigorous and independent academic research, rather that the research is undertaken with the aim of justifying and confirming already adopted political positions. Policy Exchange has devoted a lot of resources to establishing a space – on society’s margins – for Muslims in Britain. In fact, according to Peter Oborne, the think tank’s most enduring achievement has probably been the reshaping of government policy towards its Muslim citizens.

Wedded to Samuel Huntington’s “Clash of Civilisation” hypothesis, the think tank can be rightly blamed for the institutional discrimination Muslims suffer in Britain. In this issue, John Holmwood charts the slide of Muslims to subaltern status under successive Conservative governments since 2011, showing how a small group of politically motivated neo-conservatives have steered government policy towards a widely accepted securitisation of Britain’s Muslims, including of course, the expansion of the authoritarian Prevent programme. Despite the hyper-focus on Muslims, Holmwood argues that Prevent in education spheres has undermined the agency of all parents.

The restrictive space given Muslims in the public sphere of several Western countries is a theme referenced in the second article in this issue by Saeed Khan. He places it in the context of a declining Anglophone West where the pretence to the primacy of rule of law, democracy, multiculturalism and equal rights has been lifted by the resurgent forces of neo-populism, racism and nativism. As much as Western countries espouse pluralism, free expression and tolerance, their increasingly visible absence in practice exposes an anxiety borne out of political decline.

Far from heralding the triumph of capitalism as Frances Fukuyama once exulted, the demise of the Soviet Union has seen the bipolar world order sheer away in multiple, often competing, directions. This has created challenges for Muslims living in the Islamicate and Muslims living in the West. In the latter, minority Muslim communities can expect to face more scapegoating and demonisation as a result of ideological animus, but also as a convenient diversion from state failures. For the Islamicate, there does not appear to be a ready-made antithetical alternative to the West available to the Muslim world. In the absence of an off the shelf ideology, could the Muslim world be forced to go it alone? “As the Western model predicated upon liberal democracy, market economy and the nation-state finds these pillars to now be wobbly, the Ummah might gain a sense of rejuvenated optimism that it can re-emerge as a coherent, structured, even thriving polity as none of these features of the Western model are necessary for its success and survivability,” opines Khan.

At present though, this option is not on the cards, argues Zviad Jughashvili in our third essay. While some Muslims yearn for a migration to Muslim-ruled countries, this is a reflexive impulse which raises more questions than answers. Migration played a crucial role in the life of the early Muslims with the two most famous instances occurring when a group sought refuge in Abyssinia to escape persecution in Makkah and later when the Muslim community uprooted to Medina. However, we would be wrong to romanticise these episodes and transpose them to the present. In Muslim countries such as Egypt, Uzbekistan and Azerbaijan, a zealous believer is likely to draw unwanted attention from the authorities. Where it might be easier to practise one’s ritual obligations this has to be balanced against living in a society where one acquiesces in the authorities’ glaring injustices. This carries huge negative spiritual and fiqhi ramifications. All things considered, as things stand, migrating to Muslim-ruled countries is a case of jumping out of the frying pan into the fire, argues the author. If we must move, we should do so with the intention of improving the society we are going to, not just looking forward to halal food and tarawih prayers.

The traumatic upheaval that is migration forms the basis of many claims to statehood, such as that of Pakistan, which was hewn from colonial India at Partition. A huge number of Muslims in India, however, declined to leave their homeland for the new Muslim homeland and it is their worsening predicament that is the focus of our last essay by Muhammed Nihad PV. The features and rise of Hindutva, an extreme fascist ideology adopted by many Hindus and the current Indian government, have been well documented in this journal. Indeed, its spread through the Indian diaspora is fast becoming a national security priority for countries like the UK and Canada, both of which are witnessing a wave of Hindu supremacist assertiveness expressed in hostility to Muslims and Sikhs. This is a timely revisit to the subject as the last few weeks have seen Hindutva activists engage in mob violence against followers of these faiths.

Nihad analyses the ideational underpinnings of Hindutva, viewing it as an exceptionalised response to post-colonial anxieties. The absence of cultural or social homogeneity creates an ideological vacuum that is fertile ground for the projection of perpetual enmity rather than an inclusive ethos as the glue of statehood. Enemies, whether external or internal, are absolutely necessary for such a nation to survive. The antagonism towards colonialism gave way to the anti-Muslim/anti-Pakistan nationalism at the juncture of partition.

This issue has highlighted the lack of easy answers and made-to-fit solutions for world problems, notably for Muslims in whatever setting. However this uncertainty, if accepted, need not be one to be (solely) feared. Understanding that we need to work and think hard for ways to create better societies – in whatever context- is the beginning of the process of transformation. We hope you will join or even start the necessary conversations where they are needed.